Unit 4 Introduction

Many of us know someone, or have been diagnosed ourselves, with some kind of mental health condition such as ADHD, depression, or PTSD. These disorders are extremely complicated, since many arise from a mix of genetics, biology, environment, and behavior. How do we even conceptualize a mental illness? Is it a brain disease? Is it something to be cured, managed, or accepted as a difference? This section introduces the concept of a biological component to mental illness, discusses the neuroscience behind many common disorders, and raises some of the ethical and societal questions around mental health conditions.

On the other side of the coin from mental illness is the concept of well-being. Brain function is also involved in the difference between being merely healthy (no neurological or psychiatric diseases) and doing great—living a good life. In this section, we’ll also look at what neuroscience knows about the good life, as opposed to just not feeling “bad.”

Note: The University of Washington’s Neuroscience for Neurodiverse Learners Project has collected a set of helpful resources for supporting students with different mental health conditions and learning differences.

Note: The Elaborate activity for Lesson 6 in this unit requires students to collect data on their behavioral interactions for a day so they can later analyze and discuss in class. Should you choose to teach this activity, it is recommended to distribute the empathy self-reflection guide to students 1-2 days in advance.

What's In This Unit?

Section 1: Mental Health Conditions

- Lesson 1: Mental health in society

- Lesson 2: Does mental illness = brain disorder?

- Lesson 3: Disorders of development

- Lesson 4: Disorders of aging and experience

Section 2: Well-being

- Lesson 5: Personal well-being

- Lesson 6: Social well-being

Terms & Definitions: Unit 4

- Trait – A characteristic feature of a person. There are physical traits (e.g. eye or hair color) and behavioral traits (e.g. impulsivity). Another kind of trait is a predisposition to a medical condition (e.g. risk for heart disease). Both genes and environmental factors play a role in determining physical and behavioral traits.

- DNA – The material found in the cell nucleus which holds instructions for making proteins in our body. This “blueprint” for our body is the source of heredity, because some of this information from each parent is passed on to the child.

- Genes – A section of DNA that acts like a “recipe” for the proteins that make up your body, coding specific instructions for when, how much, and what proteins to make. It is thought that humans have around 20,000–25,000 genes.

- Chromosomes – DNA is compactly stored in thread-like structures called chromosomes. Each human has 23 pairs of chromosomes in each cell.

- Monozygotic vs. Dizygotic Twins – Monozygotic twins (identical twins) result from the fertilization of one egg by one sperm and share the same chromosomes. Dizygotic twins (fraternal twins) result from the fertilization of two eggs by two sperm and are not genetically identical; they are like any other pair of siblings.

- (Frontal) Lobotomy – A surgical procedure to either destroy or sever part of the frontal lobe from its connected brain regions.

- Electroconvulsive Therapy (ECT) – Pads placed on the head are used to generate a brief “storm” of firing neurons (similar to a seizure) by sending electric currents through the brain while the patient is sedated.

- Deep Brain Stimulation (DBS) – Electrical pulses are sent through electrodes that have been surgically implanted in specific areas deep inside the brain.

- Meditation – A term used to describe many types of practices related to contemplation, reflection, and relaxation. This practice comes out of both Eastern and Western religious traditions.

- Mindfulness Meditation – A type of meditation in which the person focuses on, but does not try to change, their thoughts, sensations, and emotions.

- Empathy – The ability to understand and/or share the feelings of another person.

- Compassion – A concern for the welfare of another person, often in situations of suffering.

- Cortisol – A hormone that is released in response to stress.

Section 1: Mental Health & Society

Lesson 1: Neurons

Objective: Students will be able to discuss challenging social and ethical issues in the mental health field.

ENGAGE/HOOK: Lobotomies (15 min)

Introduce the lesson by explaining the background information below and guiding them through the following activity:

To introduce this unit on mental health and mental health conditions, this lesson will consider how our perception of mental health has changed over time (or not) and how scientific practices have contributed to those perceptions. For example, frontal lobotomies were a practice used by some doctors in the 1940s and 50s to treat mental illness, especially in subjects that were deemed potentially violent. This procedure essentially severed the connections between the frontal lobes and the rest of the brain. In the days before modern drugs that can impact the brain and behavior, this surgical treatment was initially seen as a miracle. Although some suicidal patients did report that it eased their symptoms, most subjects showed permanent negative impacts. As its popularity spread, children who seemed defiant or moody were given this invasive surgical procedure in an attempt to change their personality, even in the absence of mental illness.

Ask students to complete one or more of activities below based on your class’s needs:

- Have students read this short history of lobotomies from Psych Central using the Reading for the GIST protocol.

- Show students the popular YouTube channel SciShow’s video on the history of the frontal lobotomy and what is sometimes described as the worst Nobel Prize awarded in history.

EXPLORE: Disease or Difference?

Explain the background information below to students to frame the following activity:

While some extreme practices like lobotomies are no longer used today, there are still differing perspectives about mental health conditions between scientists and society. Many people who live with mental conditions advocate for societal changes that can better support them as they are, while scientists often seek to characterize the symptoms of diseases and disorders to study underlying biological causes or possible therapies.

Guide students through the following activity analyzing different perspectives on autism:

- Have students read this article from the Washington Post: “A medical condition or just a difference? The question roils autism community.” (A longer version of this article, “In search of truce in the autism wars” by Alisa Opar, was originally published in Spectrum.)

- Then, give students the following scenario either on the board or print it on half sheets of paper:

A research study about neurodevelopmental features of autism has been accepted for publication in a major scientific journal. In the manuscript, the authors—who are neuroscientists—refer to autism as a “disorder,” and to the “symptoms” of autism. An organization that advocates for people with autism has heard of the upcoming publication, and has written to the editor-in-chief asking that the authors modify the language of the manuscript prior to publication to refer to autism as a “difference” and replace the word “symptoms” with “traits.” - Break students into groups and assign them each one of the perspectives in the table below, imagining the voices of people they read about in the Washington Post article.

- The Moderator and Editor-in-Chief have more directorial roles

- Direct students to argue whether revisions to the article are needed while considering the voice of their given perspective.

- Prompts to help students get started are also provided in the table. Students can also integrate ideas from others quoted in the article or from their own experience.

| Role | Prompt |

| Moderator | The moderator will keep the conversation focused and make sure all voices are heard. |

| Editor-in-chief of the scientific journal | The editor-in-chief will listen to each argument in turn, and come to a final decision about whether edits are needed prior to publication. |

| Neuroscientist: Manuel Casanova | “As a neuroscientist who studies neurodevelopmental disorders, my colleagues and I describe autism as a disorder because…” |

| Parent: Julie Greenan | “As a parent of children spanning the autism spectrum, I think language is complicated because…” |

| Autistic Student: Lilo | “As an autistic student, I don’t see myself as having a disorder because…” |

| Autistic self-advocate: Ari Ne’eman | “As an autistic self-advocate, I think it’s important to frame autism as a difference because…” |

| Someone with severe autism: Benjamin Alexander | “As someone with severe autism, I hope that medical researchers view autism as a disorder because…” |

EXPLAIN: Mental Health Equity

The following information is teacher-facing and can be utilized to teach students new information in whatever format works best for you and your students.

Key points:

- Our notions of mental health and what is normal are embedded within a specific culture at a specific period in time.

- People assign different values to medication versus personal responsibility in considering treatments for mental health conditions.

- Considering language in both medical and everyday contexts can help improve stigma around mental health conditions.

What is “Normal?”

Our definition of “normal” or “typical” mental health is fluid. Experiencing occasional stress, mild fluctuations in mood, or temporary emotional distress does not necessarily indicate a mental health problem. What is considered normal mental health can also vary across individuals, cultures, and even time—a trait that seems atypical today may have been neutral or advantageous at a different point in our evolutionary history. Mental health is associated with being able to regulate and manage emotions, cope with stress and adversity, form and maintain relationships with others, perform cognitive functions like memory, attention, decision making, and problem solving in everyday life, and generally feeling a sense of purpose and enjoyment. However, defining what is “normal” can be useful for identifying when things go wrong and someone needs help. The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 5th Edition (DSM-5) is the current standardized framework for the classification and diagnosis of mental disorders. It classifies mental disorders into various diagnostic categories based on symptom patterns and severity of impact. However, some concerns with the DSM-5 include its reliability and potential for applying diagnoses to normal variations in behavior.

Medical Treatments vs. Personal Responsibility

As our understanding of the neuroscience of mental health conditions advances, some argue for a greater recognition of biological factors in disorders and need for medical treatment while others argue that these factors are excuses for a person’s own choice in behavior. Is it “lazy” to take a pill rather than “tough it out” through depression or ADHD when it gets in the way of school and job performance? Should the standard for medication for psychiatric illnesses differ from, for example, Type 2 diabetes, which can be improved by diet and strenuous exercise or by medication? Given that depression saps motivation and negatively affects mood, is it reasonable to expect people to solve their problems on their own? Over the years, mental health “parity” laws have ensured that most health insurance plans must offer benefits for mental illness at the same level as medical or surgical benefits. How might this protection influence the attitudes of patients or doctors in their approach to a mental health condition?

Stigma and Language

Whether in everyday language or in how scientists and doctors communicate, the words we use influence our thoughts and beliefs. A familiar example may be “hysteria,” derived from the Greek and Latin words for uterus, which was used for centuries by physicians to dismiss women’s physical and psychological ailments. As a more prosocial example, a movement in Japan in the 1990s to rename schizophrenia from its previous name (translating to “mind-splitting disease”) to a new term (“disintegration disorder”) both reflected an updated scientific understanding of the disease and led to increased diagnosis, treatment, and acceptance. Today, there are still many terms commonly used in casual language that originated from perceptions of mental illness. These continued negative connotations can reinforce stereotypes and discourage people from seeking help.

Additional Resources

- What is “Normal?”

- This article poses the questions “What’s normal, what’s not?” as a way to introduce the DSM-5. (Mayo Clinic)

- A longer article about diverse interpretations of “what is normal?” (Psychology Today)

- Building on the Explore activity in this lesson, “Autism Research at the Crossroads” by Brady Huggett offers an update on how conflicting perspectives are shaping research. (Spectrum)

- Medical Treatments vs. Personal Responsibility

- This article advocates that considering mental illnesses as medical conditions is important for appreciating that they are treatable and not due to personal weakness. (National Alliance on Mental Illness)

- This psychology blog post argues that a framework of personal responsibility is needed to build motivation for long-term skill building and self-management. (Psychology Today)

- Stigma and Language

- This resource offers guidance on using relatable language that supports understanding, including this infographic (content warning: this resource mentions suicide). (National Alliance on Mental Illness)

- This article discusses the renaming of schizophrenia in Japan. (National Alliance on Mental Illness)

- This article describes the issue of ableist language, commonly used words, and alternatives for avoiding mental health stigma. (Verywell Mind)

ELABORATE: Awareness Poster (60 min)

Explain the background information below to students to frame the following activity:

Mental health is health! There is still social stigma, inequities in resources and support, and a lack of awareness about mental health and mental health conditions in many areas of society.

Have students break into teams and choose a community issue or mental health topic they are passionate about and create an awareness poster (or video) about their chosen issue.

Make sure that the poster includes:

- Definition of issue or topic

- Community affected

- How we can improve awareness

- A call to action for your community

Displaying the posters around the classroom or school offers a great opportunity for students to teach one another and advocate for themselves and others. An optional extension could include having students interview someone living with a mental health condition, a family member of someone who has been diagnosed with a mental health condition, or a mental health professional (such as a school counselor).

Lesson 2: Does Mental Illness = Brain Disorder?

Objective: Students will be able to discuss genetic components, current therapies, and emerging treatments for mental health conditions.

ENGAGE/HOOK: Genetics and Mental Health (10 min)

Introduce the lesson by explaining the background information below and guiding them through the following activity:

Most mental health conditions can be broken into genetic factors or environmental factors. This first lesson focuses on the genetic factors underlying some of these conditions. Most of the conditions you have likely heard of have some underlying difference in neural activity or brain function; some, but not all, of these differences are linked to genetic variation.

Break students into pairs and ask them to discuss the following using the 30 Second Expert activity:

- Brainstorm the top 5 mental health conditions you can think of.

- Each student should then choose one condition as the topic for their 30 Second Expert.

- What do you think causes or leads to this mental health condition? Biological/genetic factors? Environmental factors?

If students need a refresher on genetics, refer back to the Launch Lesson as well as these helpful resources from the University of Utah’s Learn.Genetics website:

- Introduction to heredity

- This is an introduction to traits that discusses the relationship between genes and environment on physical/behavioral traits, trait inheritance, and complex traits.

- This page gives a description of what it means to talk about genetic “risk” factors.

EXPLORE: Genetic Testing Discussion (30 min)

Explain the background information below to students to frame the following activity:

What are the positives and negatives of genetic testing for an incurable disease? Schizophrenia and Alzheimer’s disease have clear genetic components, though neither of them is a pure genetic disorder. This means that a genetic test can only ever tell you the probability of acquiring the disorder, rather than a straight “yes” or “no.” This is likely because environmental factors can make it more or less likely that a particular genetic variant will result in the condition.

Guide students through the following activity about genetic testing:

- Have students read excerpts from Still Alice, by Lisa Genova.

These excerpts cover what it is like to have this kind of genetic testing done and how it might affect your choices to have children and make other life decisions. Note that the scenario in the book involves a type of early onset Alzheimer’s disease that has a direct genetic cause; other types of Alzheimer’s disease are caused by more complex interactions between genetic, environmental, and behavioral factors. Warning: This narrative discusses death and dementia and may be emotionally intense for some students. - As an alternative to the reading, you can show students this video about learning your genetic risk for Alzheimer’s disease.

The video shares personal perspectives and results of the REVEAL Study, a project to study the emotional, behavioral, and health-related impacts of disclosing genetic risk for Alzheimer’s disease. - Lead a discussion with the class about ethical concerns regarding genetic testing.

- If someone in your family had schizophrenia or Alzheimer’s, would you choose to get tested for the genetic variant? Why or why not? (Such a test truly exists for some types of Alzheimer’s disease but not schizophrenia.)

- How do you think you would respond to finding out?

- Would your answer change if a cure were currently available?

- What if preventative treatment was available?

- If you knew you had a genetic predisposition, how might that affect your lifestyle or behavioral choices?

- Who do you think should have access to the results of genetic testing?

EXPLAIN: Genetics and Therapies

The following information is teacher-facing and can be utilized to teach students new information in whatever format works best for you and your students.

Key Points:

- Genetic studies can tell us if a person’s specific DNA may increase their risk for a given psychiatric disorder.

- Treatments for mental health conditions include biological therapies that directly modulate brain activity and behavioral therapies.

- Recent genetic research has led to the possibility of earlier diagnosis, but many brain disorders have no cure and experimental treatments are risky.

Genetic Risks and Indicators

Twin studies are a powerful tool that can be used to see how heritable—and thus, genetic—a particular condition is. If there is a genetic component to a disorder, then monozygotic (identical) twins will be more likely to share this disorder than dizygotic (fraternal) twins, assuming that twins who are raised together experience very similar environmental conditions. Twin studies have found that psychiatric conditions such as schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, autism spectrum disorders, and attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) are highly heritable. More sophisticated genetic studies are revealing patterns of gene activity that overlap between disorders—for example, expression of two genes involved with regulating calcium flow into neurons—and raise the possibility of shared therapies. Other genetic patterns are unique to a particular disorder and could be developed as “biomarkers” for early diagnosis and better treatments.

Biological and Behavioral Therapies

Biological therapies for mental health conditions include both medications and brain stimulation therapies. Medications work by altering neurotransmitter activity in the brain to regulate mood, cognition, and behavior. Among brain stimulation therapies, electroconvulsive therapy (ECT) involves passing an electrical current through the brain to trigger a brief seizure, which can relieve symptoms such as depression, mania, and psychosis. Deep brain stimulation (DBS) is a surgical procedure used to treat certain psychiatric disorders, such as obsessive-compulsive disorder. Implanted electrodes in specific areas of the brain are connected to a pacemaker-like device and deliver electrical impulses to the brain to help regulate brain activity and alleviate symptoms.

Although cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) does not directly change brain activity through medication or stimulation, it can also change brain structure and function. CBT is a structured, short-term form of talk therapy that focuses on changing negative thought patterns and behaviors. It aims to help individuals identify and modify thoughts and behaviors that contribute to their mental health issues.

Emerging Treatments

Much of the stigma attached to ECT is based on early treatments in which high doses of electricity were administered without anesthesia, leading to memory loss, fractured bones and other serious side effects. The famous example of ECT in the book and movie “One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest” shows ECT being used on a patient against their will, something that does not happen today unless the patient is already at risk of harming themselves. Today it is considered an extreme therapy, but it is much safer but still useful in some cases in which people with severe mental illness symptoms cannot find relief with other methods. More recently, there is growing interest in the potential therapeutic effects of psychedelic drugs (e.g., psilocybin, ketamine, and MDMA) on mental health conditions. Research suggests that these drugs may be effective in treating substance use disorders, depression, and anxiety. But these drugs have not yet been approved by the FDA and treatment is largely limited to patients enrolled in clinical research trials.

Additional Resources

- Genetic Risks and Indicators

- This video also explains the role of identical twins in understanding heritability. (Learn.Genetics)

- This article reviews the genetics of bipolar disorder, depression, anxiety, and schizophrenia. (Healthline)

- This website (including downloadable slides) has a chart showing the genetic risk of developing schizophrenia based on family relationships, along with other statistics and impacts. (Neurotorium.org)

- This article describes a 2018 study that revealed common patterns of gene activation between different mental illnesses. (Science Magazine)

- This article reviews the opportunities and current challenges of biomarkers and the field of precision psychiatry. (Psychology Today)

- Biological and Behavioral Therapies

- The National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH) has an extensive resource page on medications used for mental illnesses. The page describes the use of medications more generally, and then describes specific medications for schizophrenia, depression, bipolar, anxiety disorders, and ADHD.

- NIMH also has great descriptions of multiple kinds of brain stimulation therapies, including electroconvulsive therapy (ECT), repetitive transcranial direct stimulation (rTDCS), and deep brain stimulation (DBS).

- This article summarizes studies that have characterized brain changes resulting from cognitive-behavioral therapy. (American Psychiatric Association)

- Emerging Treatments

- The Mayo Clinic has a good overview of modern-day ECT, though this Scientific American article gives an overview of some of ECT’s darker past.

- As investigated in this article, should access to experimental psychedelics be expanded for patients with life threatening conditions before their therapeutic promise and effects on the brain are better understood? (Time Magazine)

ELABORATE: Treatment Report (30 min)

Explain the background information below to students to frame the following activity:

When we think about treatment for mental illness, we typically think of talk therapy or medications. But what about other treatments, most of which use some kind of electrical or magnetic current to effect change in the brain?

Guide students through a jigsaw using the steps below:

- Break students into groups of 3.

- Lead students in a jigsaw by assigning each of the following treatments to one student per group.

- electroconvulsive therapy (ECT)

- transcranial direct current stimulation (tDCS)

- deep brain stimulation (DBS)

- Ask students to research the following questions for their assigned treatment and then share out in their group of three:

- What is the history of the treatment?

- For what disorders is it currently used?

- What are the risks and benefits of the treatment?

- How is the success of the treatment measured, and what are the rates of success?

Lesson 3: Disorders of Development

Objective: Students will be able to describe some of the risk factors, symptoms, and neurological bases of common disorders of development.

ENGAGE/HOOK: Diversity of Autism Spectrum Disorders (20 min)

Introduce the lesson by explaining the background information below and guiding them through the following activity:

In this lesson we will discuss disorders that arise as the brain is developing such as autism, attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), learning disabilities, intellectual disability, behavioral or conduct disorders, obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD), depression, and schizophrenia. ASD can be expressed in many different ways and looks different for each individual.

Have students explore autism spectrum disorders (ASD) using the steps below:

- Prompt students to discuss their own previous understanding or experiences with autism spectrum disorder.

- Listen to some of the following experiences of people with autism and discuss how they are different or similar.

- Students:

- In this video produced by the Washington Post, teenager Ben shares his experiences with non-speaking autism and learning new methods of communication.

- Teenager Jason James Wilson-Kageni gives a TEDxYouth talk about his social experiences growing up with autism and learning to express himself through music (note: he begins speaking at 4:54, following his musical performance).

- Teenager Abby Edwards gives a TEDxYouth talk about living with multiple disabilities and the power of self-advocacy for autistic people and everyone.

- Savants: A minority of people with ASD demonstrate savant skills, i.e. an outstanding ability in a narrow area such as music, art, or math.

- Daniel Tammet is a highly functioning autistic savant who wrote the book “Born on a Blue Day.” (TED Talk)

- Temple Grandin is an animal scientist, advocate, and autistic savant who speaks about her childhood experience and the range of autism spectrum disorders. (CNN)

- Students:

EXPLORE: Mental Illness in the Media (30 min)

Explain the background information below to students to frame the following activity:

Characters with mental health conditions in movies or TV shows, for better or for worse, often shape our social perceptions. This report from the USC Annenberg Inclusion Initiative looked at the depiction of mental illness in 200 films and includes helpful infographics about the following trends, among others:

- Mental health conditions are rarely included in popular films.

- Mental health portrayals tend to leave out underrepresented identities of race, ethnicity, gender, and sexuality.

- Mental health is often stigmatized and trivialized, including dehumanizing language.

- The frequency of teen mental health conditions is not proportionately reflected in entertainment.

- Depictions of mental health conditions are often associated with violence.

Guide students through the following character analysis:

- Have the students find video clips from movies or TV shows that portray some form of mental illness.

- Show these videos to the class and lead a discussion with the following questions:

- Do you think this illness is accurately portrayed?

- Are other characters sympathetic or unsympathetic towards the character with mental illness?

- Is the disorder presented a good thing (e.g. superpower), a bad thing, or a complex mix?

For reference, consult lists of mental health conditions depicted in TV, books, and movies:

- The Most Realistic Movies About Mental Illness, From 'Black Swan' to 'Eighth Grade' (Collider)

- Media and The Portrayal of Mental Illness Disorders (Integrative Life Center)

EXPLAIN: Developmental Mental Health Conditions

The following information is teacher-facing and can be utilized to teach students new information in whatever format works best for you and your students.

Key Points:

- Childhood neurodevelopmental disorders are thought to be in part associated with differences in the sequence and timing of early brain development.

- Developmental disorders that arise during adolescence are likely associated with pruning and myelination processes in the teenage brain.

- Although many aspects of the basic neuroscience of brain development and maturation have been elucidated in recent years, the interactions between genetic and environmental factors underlying neurodevelopmental disorders, along with the complexity and diversity of symptoms remain poorly understood.

Childhood Neurodevelopmental Disorders

Some well-known disorders are related to early differences in the growing brain and start becoming evident in children at a young age. These include autism spectrum disorders, attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), and behavioral or conduct disorders. The development of the brain and nervous system is tightly regulated and precisely timed, driven by both a child’s genes and their environment. Before birth, neural stem cells divide, differentiate, migrate to different locations, and begin forming connections to establish the layered structure of the brain. These structures and pathways continue to develop after birth. A genetic difference or a major environmental trigger that alters the process can result in permanent differences in brain architecture or connectivity between neurons. Due to the complexity of development, there are many potential causes of these neurodevelopmental disorders that may affect different areas of the nervous system at different times and ages. As a result, scientists often don’t know why someone has ADHD, for example, and the treatments we have for these patients have been developed over time via trial and error.

Adolescence and Mood Disorders

Other common mood disorders, such as obsessive compulsive disorder (OCD), bipolar disorder, depression, and schizophrenia, may not become evident until a child is in their teens or early adult years. In addition to genetic risk factors, adolescence is a time of maturation and change in the brain—hormones influence neurotransmitter activity, myelination strengthens networks for impulse control in the prefrontal cortex, and unused connections are pruned away. Genetic or environmental disruptions with this maturation process are thought to be at least partially responsible for these disorders, but birth trauma and prenatal factors have also been linked to some of these disorders. Since the frontal lobe is undergoing a period of extreme change, scientists think the brain is therefore more plastic or open to influence from genetic and environmental factors, such as stress, trauma, or even substance use (see more information in Unit 5, Lesson 1). Treatments for all these disorders, regardless of when they arise, often involve a combination of psychotherapy, medications, and home- and school-based support programs.

Additional Resources

- This website from the National Institute on Mental Health reviews mental health issues found in children and adolescents.

- The National Alliance on Mental Illness has some overall statistics for mood disorders and mental health in all ages, including information about specific groups of people and their risk for mental health disorders (e.g. veterans, men/women, children and adolescents).

- Childhood Neurodevelopmental Disorders

- This brief video animation depicts how brain cells proliferate and migrate during prenatal development. (HHMI BioInteractive)

- Autism Spectrum Disorders

- This resource page describes the signs, potential causes, and common therapies for autism. (National Institute on Mental Health)

- Dr. Temple Grandin is one of the most famous Americans living with autism. She has written many books and been in many documentaries, and her website includes more about her expertise and experiences.

- On social media, many autistic people use the hashtag #actuallyautistic to share their individual experiences and perspectives.

- A video featuring children and teens with autism explaining the challenges they face and how they feel about the quest for a “cure for autism.” (Massachusetts General Hospital)

- Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD)

- NIMH has a helpful website about ADHD and its incidence in children and adolescents.

- This article outlines evidence that ADHD is associated with dysregulation of dopamine. (Healthline)

- Why do some children with ADHD seem to “outgrow” it while others see benefits from continued therapy and drug treatment? This article describes a study suggesting that asynchronous signaling often seen in the brain of children with ADHD can sometimes be restored in adulthood. (MIT)

- Adolescence and Mood Disorders

- Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder (OCD)

- NIMH has a website with an overview of obsessive-compulsive disorder and its symptoms, risks, diagnosis, and treatments.

- A great article about a major OCD researcher at UCLA and his use of mindfulness techniques as treatment. (Discover magazine)

- A short video of one man describing his compulsions, with a few clips of a therapist talking about her treatment approach.

- Bipolar Disorder

- NIMH has a helpful website on Bipolar Disorder and its incidence in children and adolescents.

- An Unquiet Mind, by Kay Redfield Jamison, is an autobiography of a well-known psychology researcher who has bipolar disorder.

- Depression

- NIMH has a website with an overview of depression symptoms, risks, diagnosis, and treatments.

- This online interactive textbook has a good introduction to the neuroscience of depression. Note that the serotonin hypothesis discussed here is a leading theory of the molecular cause of depression and other mood disorders, but no single theory accounts for all the symptoms and variability we see in patients. (McGill University)

- This article talks about the main regions of the brain thought to play a significant role in depression and discusses genetic research into both the causes and best treatment methods for depression. (Harvard Medical School)

- Schizophrenia

- NIMH has a website with an overview of schizophrenia symptoms, risks, diagnosis, and treatments.

- This article discusses research on a genetic test that may predict risk of schizophrenia. (Broad Institute)

- Elyn Saks describes her experience living with schizophrenia in her TED Talk: “A tale of mental illness—from the inside.”

- Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder (OCD)

ELABORATE: Pharmaceutical Ads (45 min)

Explain the background information below to students to frame the following activity:

Often, biological causes of a disorder are oversimplified. This may be helpful, as we still have much to learn about the neuroscience of mental illness, but sometimes it may do more harm than good, if these simplified explanations lead to false inferences or conclusions about causes and treatments.

- Have students look up medication ads for a given disorder (e.g., pharmaceutical ads for depression, schizophrenia, or bipolar disorder).

- Ask students to present these ads in class.

- Lead a class discussion with the following questions:

- How is the ad supposed to make you feel? Why do you think it might appeal to someone with symptoms of the disorder?

- What do we know of the neuroscience behind this disorder? What evidence can you find about the drug’s efficacy?

- What are potential side effects of the drugs?

- Is the ad simplified or inaccurate?

- How would you change the ad to better reflect an accurate understanding of the disorder?

Lesson 4: Disorders of Aging & Experience

Objective: Students will be able to describe some of the risk factors, symptoms, and neurological bases of common disorders of aging and experience.

ENGAGE/HOOK: PTSD (10 min)

Introduce the lesson by explaining the background information below and guiding them through the following activity:

Just as many disorders of the brain that relate to mental health arise during childhood and development, other brain disorders occur only late in life due to either problems with aging or particular experiences. This lesson will discuss these types of disorders including post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and Alzheimer’s and traumatic brain injury.

Dissociation is a psychological phenomenon often observed in individuals with PTSD. When a person experiences intense trauma, their mind might attempt to distance itself from the traumatic event as a way to reduce the immediate emotional impact. It involves a disconnection or detachment from one's thoughts, feelings, memories, sensations, or even their sense of identity, surroundings, or reality. This can lead to a feeling of being "outside" oneself or experiencing events as if they are happening to someone else.

Guide students through the discussion below about PTSD:

- Show this video of a first-person account of living with PTSD.

- Ask them to reflect on the questions below after the video:

- How does Sarah explain what it feels like to have a dissociative episode?

- What are some of the ways Sarah describes to manage her dissociative episodes?

- How might Sarah’s daily life and plans for her future be influenced by PTSD?

- Sarah says “you can’t force your brain to unlearn trauma.” Based on your current understanding of the brain, what do you think this means?

EXPLORE: Case Studies (30 min)

Guide students through the activity below in order to introduce some disorders of aging and experience.

- Read each case study below from the left hand column to the class.

Ask the class to guess what disorder might be described. (correct answers in middle column)

Case study Disorder Resources “A 42 year old man has been filling his entire week with work and hobbies to keep himself busy and his mind occupied. Although he lived through a major earthquake 8 years ago and witnessed several people get injured, he tells his friends and family that it did not impact him. He tends to avoid people that knew he had gone through this experience and quickly changes the topic when it comes up. However, he finds that whenever he has free time, he has unwanted intrusive thoughts and images about the earthquake. In addition, he has distressing nightmares that are causing him to lose several hours of sleep each night.” PTSD An article about a soldier who suffered from PTSD after his deployments. The story also has some statistics of PTSD among veterans. (SFGate)

The American Psychological Association has a page of case studies of PTSD.

“This 75-year-old female patient comes in with her 40-year-old son. The son reports that his mother has been forgetting recent events. She also began experiencing irrational emotions. Later on, she would confuse the names of relatives and would become confused while doing simple tasks such as brushing her hair.”

Alzheimers Written by high school teachers, this is a long and detailed lesson plan using Alzheimer’s case studies (video links hosted by PBS can be found inside) to teach about the degeneration of the brain seen in this disease. (Centers for Disease Control & Prevention) “A 40-year-old man suffered a head injury in a motor vehicle accident. He is married with a family and had maintained full time employment for a number of years as a teacher before the accident. He complained that since his injury he is forgetful, loses things, has difficulty finding the right word to say, and feels uncomfortable in social situations but manages better in one-to-one situations.”

Traumatic Brain Injury This website targeted at therapists has several case studies about TBI patients to examine, such as this one. (NSW Agency for Clinical Innovation)

- After the class guesses which disorders are being mentioned ask them to complete a written reflection:

- Were you familiar with any of these disorders already from your own life or your family?

- How did some of these case studies differ from the disorders of development in the previous lesson?

- As these disorders occur later in life, how do you think the person with the disorder experiences and processes these changes vs. someone born with a brain disorder?

- Optional: Have students pair and share their reflections with each other.

EXPLAIN: Mental Health Conditions of Aging & Experience

The following information is teacher-facing and can be utilized to teach students new information in whatever format works best for you and your students.

Key Points:

- Disorders of aging, such as Alzheimer’s or Parkinson’s diseases, are associated with the spread of misfolded proteins that cause cell death.

- Disorders of experience, such as PTSD or traumatic brain injuries, are initiated by psychological or physical trauma.

- Genetic and environmental factors can increase a person’s risk for disorders of aging and experience.

Disorders of Aging

Aging is the main risk factor for some common brain diseases, but these disorders are more than just the natural slowing down of cognition that we expect to see with age. While Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s diseases are generally thought of more as neurological disorders than mental illness, they affect many people in our society. In these “neurodegenerative” diseases, the neurons of a particular part of the brain begin dying off first, leading to a particular pattern of symptoms. In Parkinson’s disease, cells that produce the neurotransmitter dopamine deep in the brain die off for unknown reasons. At first, this causes problems with movement (like tremors, trouble walking, or stiff muscles) in regions that rely on dopamine to function, but cell death can eventually spread to other regions. In Alzheimer’s disease, cell death starts in the hippocampus, leading to particular symptoms related to memory. Eventually, the disorder spreads to many areas of the cerebral cortex responsible for tasks such as language, reasoning, and social behavior, creating a wider range of symptoms as the disease progresses. There are currently some treatments that can slow down the progression of these diseases, but no real cures. However, in both disorders, misfolded clumps of protein spread throughout the brain, which are targets for potential treatments. Scientists are also beginning to use brain scans like PET to look for these protein clumps in the brains of living patients. In the future, this may be a method of diagnosing patients based on more than just their symptoms.

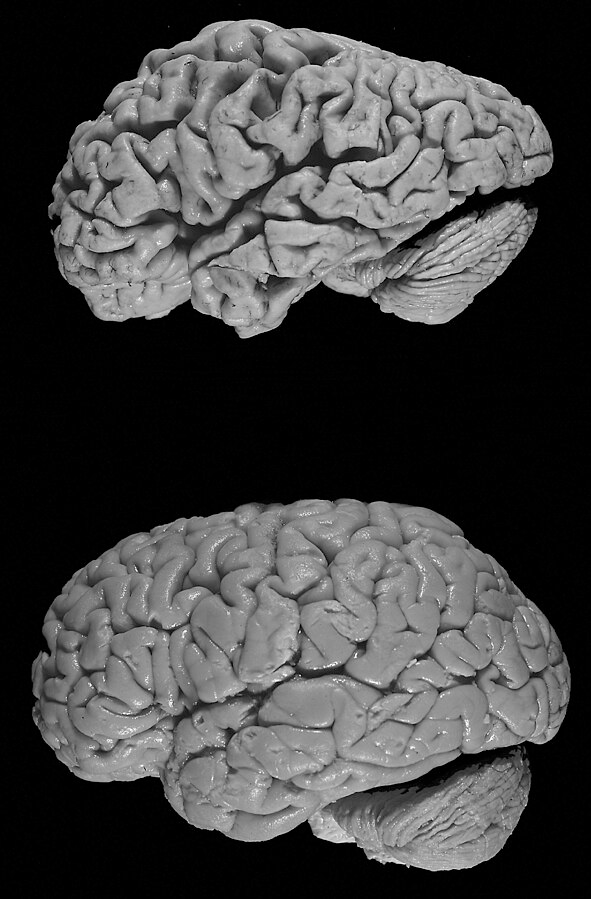

Compare a healthy brain (bottom) to the brain of a donor with Alzheimer's disease (top). As cell death spreads to different regions, the brain appears to shrink in size. Image credit: Hersenbank/Wikimedia Commons. This file is licensed under the Creative CommonsAttribution-Share Alike 3.0 Unported license.

Disorders of Experience

Other mental health conditions that develop later in life are due to physical or psychological trauma, such as post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) or traumatic brain injury (TBI). These conditions can also be influenced by a mix of genetic and environmental factors. Certain genes or biological conditions can make someone more vulnerable to developing PTSD than other people. Scientists believe that patients with PTSD have an overactive amygdala driving these emotional responses and not enough activity in their frontal lobe to dial back down these responses. TBI can vary widely with the exact type of injury and where it is located in the brain. Some types of injuries are caused by a deep or penetrating injury to a particular area, others are due to a widespread jolt to the brain. The most common type of TBI is caused by a minor blow to the head and/or a concussion. There may be some genetic factors that contribute to individual differences in impact of and recovery from TBI, but these are not well understood.

Researchers continue to study the connections between PTSD, TBI, and neurodegenerative diseases. Armed service members and veterans who have seen active combat are common patients to be diagnosed with PTSD, TBI, or both. There is also an association seen between severe TBI and later diagnosis of dementia, which can be seen in accident victims, veterans, and some professional athletes. Research has connected TBI to dementia through symptoms that may resemble, but are not directly connected to, Alzheimer’s disease or other aging-related diseases. However, there is a connection between TBI as seen in professional or elite athletes (including football players, soccer players, volleyball players, and boxers) and a neurodegenerative disease called chronic traumatic encephalopathy or CTE.

Additional Resources

- Disorders of Aging

- Alzheimer’s & Parkinson’s diseases

- The National Institute of Aging has useful websites covering the basics of Alzheimer’s diseaseand Parkinson’s disease.

- This video reviews the cognitive changes in healthy aging vs. Alzheimer’s disease and recent research on the causes and risk factors of the disease. (The Franklin Institute)

- This article covers clear but detailed information about some of the known genes related to Alzheimer’s disease. (Mayo Clinic)

- This article from 2023 describes a promising biomarker test for Parkinson’s disease based on misfolded proteins. (CNN)

- Advocacy organizations share the perspectives of caregivers, researchers, and people living with disorders of aging, including stories about Alzheimer’s disease (Alzheimer’s Association) and stories about Parkinson’s disease (Parkinson’s Foundation).

- Alzheimer’s & Parkinson’s diseases

- Disorders of Experience

- Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD)

- A helpful website from NIMH with good information about potential risk factors and the neural basis of PTSD.

- This booklet describes PTSD and its symptoms, sample screening questions, and possible treatments. (National Center for PTSD)

- This collection of articles gives an overview of research on PTSD and the brain. (BrainFacts.org)

- Traumatic Brain Injury (TBI)

- This interactive website shows the details of what symptoms would be caused by TBI to each region of the brain. (Brainline.org)

- This 2023 article reports that over 90% of autopsies performed on former NFL players have revealed evidence of chronic traumatic encephalopathy, regardless of whether they were diagnosed with TBI during life. (U.S. News)

- The Military Health System shares stories of service members and veterans who experienced traumatic brain injuries and their caregivers.

- In 2023, the first post-mortem study clearly showing CTE in a young female professional soccer player (who died at 28) was published, making it clear that this disorder is not limited to boxers or professional American football players used to hard, repeated hits to the head.

- Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD)

ELABORATE: Football and Traumatic Brain Injury

Explain the background information below to students to frame the following activity:

In this next activity, you will first read an article about football injuries and chronic traumatic encephalopathy (CTE). You will then observe datasets of pathologists’ post-mortem analysis of football players who died after experiencing head injuries to look at how CTE affects the brain and answer some reflection questions. These case studies have been published by the UNITE Brain Bank at Boston University (BU) with consent from named players’ families.

- Direct students to complete the TBI Case Study Student Packet which includes the abridged article, brain images, and questions.

- After students complete the worksheet guide them through a whole group discussion using the prompt and questions below:

A student in your class makes the following claim: “The risk for injury is part of what makes football thrilling and entertaining.”- How can we explain to this student why the risk of traumatic brain injury is such a concern in football?

- What evidence from the case studies can support our argument?

- Can you think of rules or policies that could both protect players and maintain the “essence” of football?

Section 2: Well-Being

Lesson 5: Personal well-being

Objective: Students will be able to give examples of individual practices and habits that affect the brain and can improve our level of mental well-being.

ENGAGE/HOOK: Mindfulness Video (10 min)

Introduce the lesson by explaining the background information below and guiding them through the following activity:

This lesson focuses on choices, actions, and habits of mind that we can develop at an individual level to positively impact mental health. Mindfulness meditation is one evidence-based practice that students may not have experienced.

Mindfulness meditation involves the practice of “mindfulness”: focusing on current thoughts, sensations, and emotions—not trying to change them, just being aware and accepting of them. This is a practice that benefits your body by reducing stress but has also been shown to alter the brain as well, changing the structure and function of some key regions related to memory, attention, and emotional regulation. Just like getting in shape physically, it takes work and focus to get in shape mentally!

Guide students through the following intro activity:

- Begin by asking students what they know or have heard about mindfulness meditation.

- Show students this video from Scientific American that summarizes some of the psychological and neuroscientific research on mindfulness meditation.

- Ask students to think about the following questions while you watch:

- What are some of the specific benefits of mindful meditation mentioned in the video?

- How are Buddhist monks’ brains different and how does this relate to mindfulness?

- What are some other parts of the brain that change due to meditation?

EXPLORE: Mindfulness Meditation (15 min)

The best way to understand mindfulness meditation is to try it out! Guide students through the meditation and reflection below:

- Ask students to try this 5-minute guided mindfulness meditation.

- After the 5 minutes are over, ask students to answer the questions below:

- Is this what you were expecting?

- Did you enjoy the experience?

- Do you feel more relaxed or different in any way?

- What were the important elements of this exercise? What were you instructed to do and think?

- How do you think this helps your brain?

EXPLAIN: Personal Well-being and the Brain

The following information is teacher-facing and can be utilized to teach students new information in whatever format works best for you and your students.

Key Points:

- Mindfulness meditation can lower stress and improve brain activity, although its effects on brain structure are still being studied.

- Exercise has a beneficial effect on cognition, learning, and memory, and these effects can be seen in brain activity.

- Thoughtful use of technology, combined with techniques for managing distraction, can enhance the positive impact of technology on the brain.

Does Meditation Change the Brain?

Meditation is good for mental health, but researchers do not yet fully understand the mechanisms by which it works. While changes in brain structure have been observed in expert meditators, a recent study found no evidence of structural brain changes following an 8-week meditation program (in contrast to earlier studies using less rigorous methods). Long-term meditation practice, like those mentioned in the Scientific American video above, may be required for more significant structural changes. In terms of brain function, however, brain imaging shows evidence for improved function in brain areas associated with experiencing and regulating emotion and pain, while other studies have shown that meditation can affect gene expression and reduce cortisol levels to lower stress and inflammation.

Physical Exercise for Your Brain

Exercise is good for your body, but it’s also great for your brain. Exercise increases levels of brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF), a protein that promotes the growth of new brain cells in the hippocampus—a possible mechanism for boosting long-term memory. It also stimulates the release of endocannabinoids, which are neurotransmitters that promote learning through modifying neural connections. Cognitively, regular exercise has been shown to substantially benefit our ability to learn and remember information and support the development of goal-setting and coping mechanisms.

Technology and the Brain

Thoughtful use of technology can be beneficial for mental well-being—particularly activities that require active engagement, such as interacting with friends and family, learning new information from videos, or being creative. Activities that are passive, like scrolling through social media or distracting from other tasks, are more associated with negative feelings of sadness, envy, and loneliness. It’s also important to consider the impact of your technology habits. Switching back and forth between tasks results in sacrificing accuracy or efficiency, while the constant availability of technology can overload the brain on decision making and immediate rewards.

Additional Resources

- Does Meditation Change the Brain?

- This article describes a 2022 study at the University of Wisconsin along with other studies that are shaping our changing understanding of how meditation affects the brain. (Inverse)

- This website has a helpful summary of the potential health benefits of meditation, with the caveat that many research studies are preliminary or have methodological concerns. (National Institutes of Health)

- This 2017 article reports on evidence that mind-body exercises, including meditation, yoga, and tai chi, appear to suppress genetic activity that promotes inflammation. (Time Magazine)

- Physical Exercise for Your Brain

- This article summarizes the benefits of physical exercise on multiple aspects of brain health. (BrainFacts.org)

- This article discusses recent research into exercise and human cognition. (Cleveland Clinic)

- This article describes an analysis of brain imaging data from the long running Adolescent Brain Cognitive Development (ABCD) Study, which found that more exercise in children is associated with more efficient and flexible brain network function. (Boston Children’s Hospital)

- Technology and the Brain

- In this 2020 article, the authors review how technology and social media influence the adolescent brain. (Frontiers for Young Minds)

- This 2022 article describes research in children suggesting that playing video games can help strengthen impulse control and memory, reflected in higher brain activity in those regions of the brain compared to children who never played. (National Institutes of Health)

- Can technology become addictive? As summarized in a 2022 article, the problematic use of internet apps involve brain circuits related to reward and compulsion similar to those involved in substance use disorders, but a key distinction is that internet use does not cause direct neurotoxic damage. (Technology Networks)

- In this excerpt from The Distracted Mind: Ancient Brains in a High-Tech World, Adam Gazzaley and Larry Rosen suggest practical ways to manage the distractions of technology, such as tracking time spent on different apps, closing unused windows and programs, turning off notifications, putting phones away at night, and scheduling mental breaks for yourself.

ELABORATE: Making Decisions for Well-being (30 min)

Explain the background information below to students to frame the following activity:

Setting goals and making good decisions that support personal well-being can be hard, especially for teenagers whose brains are still developing. In her book How To Decide, decision scientist and former professional poker player Annie Duke offers tools to help people of all ages set goals and increase their likelihood of success.

Have students complete the following activity based on Annie Duke’s tools:

- First, have each student write down an achievable personal goal with respect to one of the three aspects of mental well-being discussed above: mindfulness, exercise, or technology. What is a reasonable time period for achieving that goal?

- Next, have them think through a premortem: Imagine yourself at that time in the future, and you didn’t meet your goal.

- List up to five reasons why this happened because of your decisions and execution.

- List up to five reasons why this happened because of things outside of your control.

- Then, have them try backcasting: Imagine yourself at that time in the future, having succeeded at achieving your goal, and looking back at how you succeeded.

- List up to five reasons why you succeeded because of your decisions and execution.

- List up to five reasons why you succeeded because of things outside of your control.

Optional: Post the goals anonymously around the classroom to inspire students by seeing their peers’ aspirations. Another option is to have students keep track of their goals privately and revisit later in the year to check on their progress or revise their goal.

Lesson 6: Social Well-Being

Objective: Students will be able to give examples of how our level of mental well-being is supported by our engagement with others.

Reminder: The Elaborate activity for this lesson requires students to collect data on their behavioral interactions for a day so they can later analyze and discuss in class. Should you choose to teach this activity, it is recommended to distribute the empathy self-reflection guide to students 1-2 days in advance.

ENGAGE/HOOK: A Good Life (15 min)

Complete the following activity with students to get them thinking about social well-being:

- Pose the following questions to students:

- What is the difference between just getting by and living a good life?

- What role do things like friendship, spirituality, helping others, gratitude, mindfulness, and physical health play in well-being?

- Hand out or display a selection of quotes: “What makes for a good life?”

- Ask students to pick one they like or to provide their own quotes.

- Have students form groups according to which quote they liked the best.

- Have students discuss in their small groups why the selected quote reflects their values.

EXPLORE: Friendship in the Brain (30 min)

Guide students through the following activity (adapted from this lesson plan on friendship and mental wellness from the Stigma-Free Society) to help them reflect on their friendships.

- Start off by getting your students to write down some of their happiest memories - just a few lines that bring them back to happy moments in their lives.

- “I was happiest when…”

- “I am happiest when…”

- Ask students to reflect on who they were with when those memories occurred.

- Ask these questions to spark conversation:

- Were they alone?

- Were they with friends?

- Which friends were they with?

- Why were those memories happy?

- Was it because of their friends?

- Show students the video “The critical importance of friends on your happiness.”

- Use these guiding questions to spark discussion:

- Why are friendships important?

- How can friendships support our mental health?

- How can friendships increase your sense of belonging and purpose? Describe a time when a friend helped to:

- Boost your happiness and reduce your stress

- Improve your self-confidence and self-worth

- Cope with trauma

- Change or avoid unhealthy lifestyle habits, such as excessive drinking or lack of exercise

- Put your problems in context to develop a stronger sense of meaning and direction

- Increase feelings of security and help protect against stress

- Ease the emotional impact of difficulties and offer new ideas about tackling them

- Finally, have students work in small groups to consider this friendship scenario and make connections to the brain:

Jazmine and Asha are good friends, but Asha dislikes how Jazmine sometimes makes mean comments about her appearance. She doesn’t feel comfortable confronting Asha about this. When she finally decides to, Jazmine listens attentively and says she didn’t realize she was hurting Asha. She apologizes for her behavior and they talk about how to make their friendship stronger.- Which brain processes might be active for each friend in this scenario?

- How is each friend thinking, feeling, and acting?

EXPLAIN: Social Well-being Research

The following information is teacher-facing and can be utilized to teach students new information in whatever format works best for you and your students.

Key Points:

- Social interaction generally improves health, including neurological health, while loneliness has been shown to have detrimental effects on behavior and the brain.

- Giving and generosity can evoke pleasure by means of the same reward circuits that are also active when receiving good things (e.g., food, money).

- Empathy is a specific cognitive function that develops over time and can be trained and strengthened for compassion.

Friendship vs. Loneliness

Research suggests that the number of friends and social connections we have relates to our overall health, perhaps due to lowered stress and increased resilience to disease, damage, or other problems. For example, studies in humans have found that there is a lower risk of dementia among women with larger social networks, and that even holding a loved one’s hand (as compared to a stranger) when faced with the risk of an electric shock actually reduces stress responses in the body and brain. Meanwhile, loneliness seems to have the opposite effect. In mice, social isolation leads to a reduction of myelin in brain regions associated with emotions. With humans, where we can better identify loneliness compared to just physical isolation, loneliness seems to affect the body’s response to inflammation, which in turn influences cognitive functions and other processes.

Giving and Gratitude

Gratitude for the good things in one’s life and giving to others can improve health in people living both with and without mental health concerns, although researchers are still investigating how and why. In the brain, generous behavior has been linked with activating the reward regions of the brain and increasing levels of dopamine and serotonin. Gratitude can also reduce negative emotions, pain, anxiety, and depression, while improving sleep and stress regulation. The positive effects of gratitude take time to develop but may have potential lasting impacts on brain activity. Keeping a gratitude journal is a simple way to practice this habit.

Empathy and Compassion

Empathy seems like a fuzzy concept, but brain imaging has given us insight into how our brain thinks about others. A specific area of the brain (the right supramarginal gyrus) is involved with how we process other people’s mental states—when activity in this region is disrupted, it is harder for people to imagine the emotions that someone else is feeling. This ability to distinguish between your own perspective and others’, as well as to predict and interpret the actions of others, is known as theory of mind. Children gradually develop theory of mind in stages as they learn from patterns of interaction, communication, and response. Empathy also extends to compassion—the recognition of and desire to help ease someone else’s suffering. Research has shown that compassion can be trained and strengthened through practice, with accompanying brain changes in areas responsible for empathy, emotion regulation, and positive emotions.

Additional Resources

- Friendship vs. Loneliness

- This website summarizes the health benefits of social connectedness. (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention)

- This TED-Ed video describes how the dynamic changes in the teenage brain shape how you connect and form lasting friendships during adolescence. (TED-Ed)

- This 2020 article summarizes a number of interesting research studies on social isolation, including studies of people working in remote places and incarcerated people in solitary confinement. (The Scientist)

- This article describes Harry Harlow’s foundational—though unethical—experiments with monkeysdemonstrating the importance of affection for normal childhood development. (VeryWell Mind)

- Giving and Gratitude

- This 2021 article discusses a number of research studies exploring the neuroscience and psychology of giving to others. (Big Think)

- An interview from 2014 summarizes research showing that people experience more happiness when giving to others, not keeping for themselves. This is seen even in young children, suggesting that happiness in giving may be “hard-wired.” (NPR)

- This 2019 article reviews research on the impact of gratitude on the brain and mental health. (PositivePsychology.com)

- The Greater Good Science Center at UC Berkeley has a simple guide to keeping a gratitude journal.

- Empathy and Compassion

- This article describes the Max Planck Institute study that discovered the critical role of the right supramarginal gyrus in empathy. (Neuroscience News)

- This video explains how children develop theory of mind and why this skill is often delayed or absent in people with autism spectrum disorder. (BrainFacts.org)

- Loving-Kindness meditation (LKM) is a technique that has been shown to reduce stress and increase empathy and compassion. See this article that summarizes its benefits and introduces its practice. (PsychCentral)

ELABORATE: Empathy and Well-being (30 min)

Explain the background information below to students to frame the following activity:

What is empathy, exactly? Researchers often distinguish between two types of empathy involved in social interactions: cognitive empathy (identifying and understanding someone else’s emotions) and affective empathy (responding to and sharing someone else’s emotions).

Guide students through this empathy reflection. A day or two in advance of this lesson, give students this empathy self-reflection guide to record their positive and negative interactions over the course of a day (adapted from an activity developed by the Ashoka Changemaker Schools).

- In class after students have filled out the reflection guide on their one, have small groups discuss the interaction questions on the handout.

- As a class, ask students to reflect on their practice of empathy using the general empath questions on the handout. What were some things that either made it easy or difficult for you to practice empathy?

- To help students connect their experiences to broader themes, explain that research suggests that the following factors can influence the practice of empathy:

- Emotion - if a person is experiencing either a positive or negative emotional state, it is harder to empathize with someone who is experiencing a different emotion

- Time constraints - it is harder to empathize with someone else when a person is faced with having to make a quick decision

- Group identity - a person is more likely to empathize with someone with whom they have a shared social identity (e.g., religion, nationality, socioeconomic class, political party, etc.

- Loyalty - a person is more likely to empathize with a friend or family member than someone who is more socially distant

For more information about the Neuroscience & Society Curriculum, please contact neuroscience@fi.edu.

Neuroscience & Society Curriculum

Launch Lesson • Unit 1: Neurons and Anatomy • Unit 2: Education and Development • Unit 3: Current Methods in Neuroscience • Unit 4: Mental Health and Mental Health Conditions • Unit 5: Drugs and Addiction • Unit 6: Law and Criminology • Unit 7: Future Technologies

This project was supported by funding from the National Institutes of Health Blueprint for Neuroscience Research under grant #R25DA033023 and additional funding from the Dana Foundation. Its content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of NIH or the Dana Foundation.