Positioned behind The Franklin Institute at the corner of 21st Street and Race Street in Philadelphia is a unique artifact that dates to the height of the Space Race and has particular importance in the legacy of NASA’s Apollo program that successfully landed twelve individuals on the Moon between 1969 and 1972.

On loan from the Smithsonian National Air and Space Museum, The Apollo Lunar Module (LM) Structural Test Model manufactured by Grumman Aerospace has resided in our Science Park since 1976 and is a full-scale representation of the spacecraft that was used by NASA to conduct the lunar landings of Apollo 11, Apollo 12, Apollo 14, Apollo 15, Apollo 16 and Apollo 17.

This structural test model was not built to be flown to the Moon. As the Apollo Lunar Module was the first manned spacecraft to be designed exclusively for use outside of the Earth’s atmosphere, which led to a number of unique challenges in its design. The LM needed to be compact and use house of the most sophisticated equipment of its time, but, in the absence of air resistance in space and on the Moon, it did not need to be aerodynamic at all. The object at The Franklin Institute was, instead, used by the engineers as they experimented with the design of the module and how it would eventually fit into the Saturn V Rocket and make its way 238,900 miles (384,472 km) to the Moon.

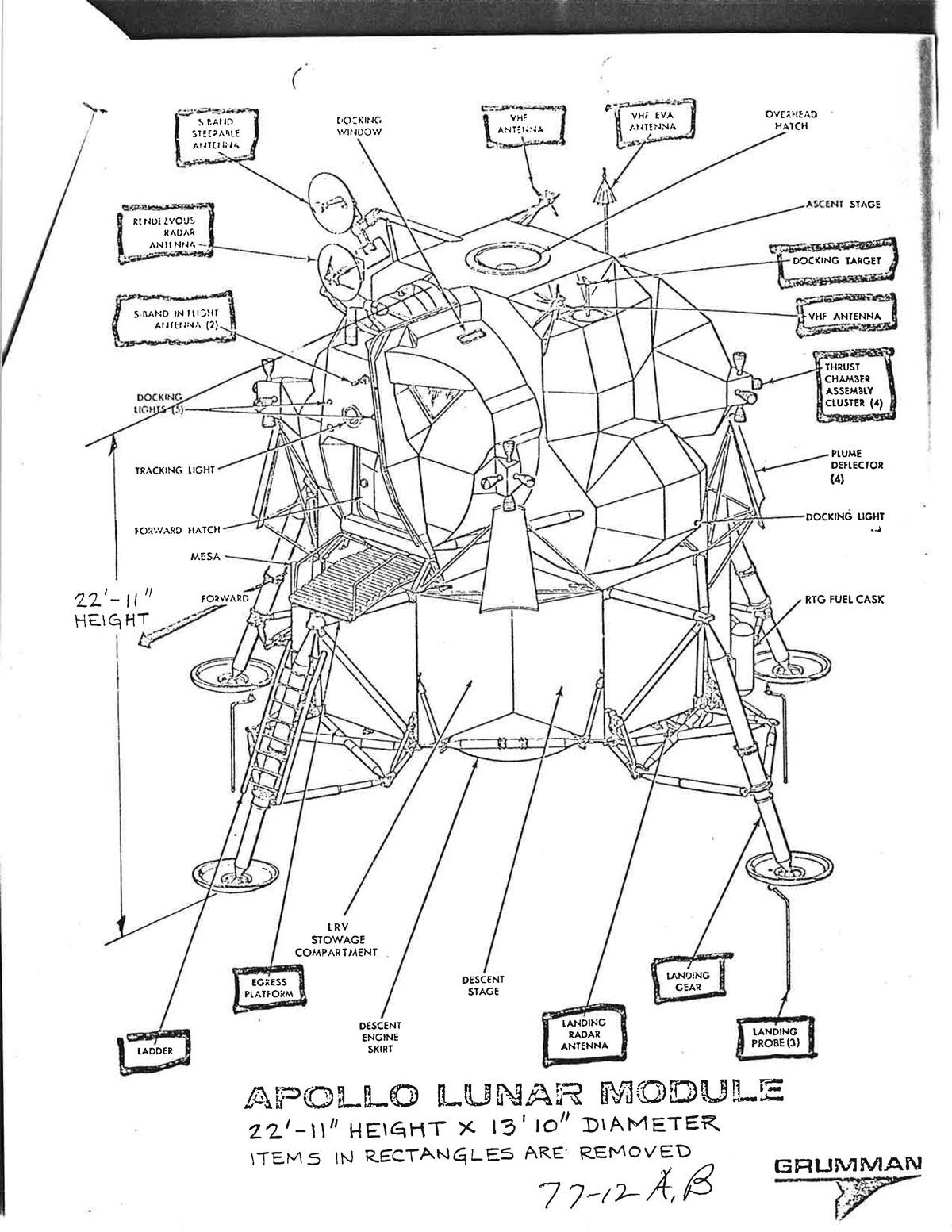

Weighing in at 33,000 pounds (14,900 kg), The Apollo Lunar Module had 235 cubic feet (6.7 cubic meters) of interior space for a crew of two astronauts. These battery powered spacecraft were designed for 75 hours of use on each flight.

The upper part of the LM, known as the Ascent Stage, would have housed the crew cabin, controls, air, water and the ascent engine that would launch the astronauts back to rendez-vous with the Command Module that would take them back towards Earth. The official designation of our structural model is LTA-3A. As the engineers were developing the Apollo Lunar Module, this ascent stage was used in structural integrity tests.

The lower part of the spacecraft is the Descent Stage where science equipment and support materials were stored in addition to the LM’s landing gear and, in the case of Apollo 15, 16 and 17, it was in the Descent Stage where the Lunar Roving Vehicle was stored. Parts of the descent stage for our lunar module, designated LTA-3DR/1, was possibly intended for use in flight as part of LM-6, but instead used for testing and engineering the spacecraft that would eventually travel to the Moon.

Of the ten Apollo Lunar Modules that flew in space, none returned to Earth. The Descent Stages all remain on the Moon where they landed and the ascent stages were either intentionally crashed onto the lunar surface, burned up in the Earth’s atmosphere or, in the case of the LM from the Apollo 10 mission, remains in a solar orbit. Apollo Lunar Modules on view in museums today are either replicas, objects like ours that were created as part of the engineering process, or were built for further lunar missions that ultimately did not take place.

The Apollo Lunar Module was flown by each mission’s Commander. The Lunar Module Pilot was tasked with monitoring the equipment and providing the Commander with all the information needed to fly the spacecraft.

After separating from the Command Module (CM), the initial lunar landing approach was flown by computer using Doppler radar during a 30 second burn to reduce speed and decrease altitude to 50,000 feet (15,240 meters), 260 miles (418.5 kilometers) from the landing site. The next burn brought forward and vertical velocity to near zero with the astronauts on their backs. At 700 feet ( 213 meters) altitude and 2000 feet (610 meters) from the landing target the spacecraft was tipped up so the astronauts could see the intended landing target and manual control was enabled for the commander to make any necessary corrections. Probes measuring 5.5 feet (1.7 meters) extended beneath 3 of the 4 footpads and would indicate when surface contact was made and would initiate engine shutdown.

The Ascent Engine had to fire just once – to lift the astronauts off the surface of the moon to rendezvous with the Command Module for the return trip to earth. If the Ascent Engine didn’t fire, those astronauts would have been marooned on the moon. Fortunately, The Apollo Lunar Module performed perfectly on each mission; it was the only flight component to not suffer a failure of some type.

A group of Grumman Aerospace retirees and employees volunteered their time and labor to rebuild this Apollo Lunar Module Engineering Model for display at The Franklin Institute. The LM restoration team dubbed themselves "The Spacecats" just for this project. Another example of their versatile restorative skills—a U.S. Navy/Grumman F4F Wildcat, a World War II fighter airplane, that is on view in the Smithsonian National Air and Space Museum in Washington, D.C.

The Restoration Team consisted of the following Grumman employees and retirees: William Adams, George Black, Charles Chlanda, Helen Chlanda, Fred Ciento, John DuDonis, Vinnie Emanuele, Anthony Ferrarioli, Milt Guttenberger, Gus Henriksen, Chris Herrnkind, John Kacinski, John Kost, William Murdoch, Joe Oliver, Joe Riccobono, Charles Salerno, George Smith, Charles Staffeldt, Sid Steele, and Joe Stryjewski. Project Director: Jake Bussolini; Consulting Engineer: Bob Specht; Administrative Assistance: Erwin McCalla, Steve Kiss, and Karl Watjen.

The Grumman Corporation was founded on December 6, 1929 and had its headquarters in on Long Island in Bethpage, New York, where the LMs were manufactured. Grumman merged with the Northrop Corporation in 1994 to form Northrop Grumman and, in addition to numerous military and civilian aircraft, the company is also well known as the manufacturer of the Grumman LLV, which is the most common vehicle used to deliver mail by the United States Postal Service.

In addition to the Apollo Lunar Module Engineering Model, The Franklin Institute is home to an actual Moon Rock that was collected during the Apollo 15 mission and a variety of objects relating to space exploration that are on view in our Space Command exhibit.

Learn more about science of space with our astronomy resources page.

Look to the sky and discover the wonders of outer space in The Franklin Institute's Space Command exhibit!