Introduction

Though he never finished high school, Orville Wright had successful business ventures in printing, bicycle repair and manufacture, and aviation. By 1896, aviation progress was happening independently around the world. In Dayton, Ohio, Orville and his brother Wilbur combined their bicycle work with inquiry and experimentation on flying machines.

Who was Orville Wright? What were his contributions to the art and science of aviation?

Aviation Science

Orville Wright, the fourth child of Milton, a circuit preacher and theology professor, and Susan, college-educated and gifted in mathematics, was born in Dayton, Ohio, on August 19, 1871. Closest to him in age were Wilbur, four years older, and Katharine, three years younger. A cultivated and happy childhood came to an end with the death of his mother in 1889; Orville left high school before his senior year while Wilbur gave up on hopes to attend college at Yale. Using knowledge gained from a summer apprenticeship, Orville started a weekly (soon to be daily) newspaper. It failed, prompting him to join a printing company in partnership with Wilbur. An enthusiast of the new cycling fad, Orville next opened a business in bicycle repair and manufacturing in 1894; the successful Wright Cycle Company eventually replaced the printing venture. This was the point, in 1896, that the brothers developed an interest in the very new science of aviation.

Progress

Advancements in aviation were already being made by 1896 in locations far from Ohio, like Penaud's models and Giffard's dirigibles in France, Lilienthal's glider experiments in Germany, Langley's powered flight efforts in Washington, D.C., and Chanute's technical data collection in Indiana.

In Dayton, Orville and Wilbur combined their bicycle work with inquiry and experimentation on flying machines. When the bicycle business slowed at each summer's end, they took their inventions to Kitty Hawk, North Carolina for testing in the open, windy terrain. From 1899 to 1903, through experiments with kites, gliders, and pilot practice, the brothers finally achieved their goal of controlled, continuous flight in December, 1903.

Established

The brothers continued to refine their invention and give demonstrations to potential customers, Wilbur in France and Orville in the United States. In a crash during a demonstration, a passenger observer was killed and Orville's serious injuries required a long hospital stay. By 1908, they were ready to establish the Wright Aircraft Company and begin to manufacture airplanes; the U.S. government was their first customer. Orville, less business-inclined, ran the factory operation while Wilbur served as president.

Almost immediately, Orville had to deal with the first of many competitors who infringed on the Wright's carefully protected patents. The resulting lawsuits continued for many years beyond Wilbur Wright's death in 1912. The verdict, confirming Orville's position that the Wrights invented controlled flight, came in 1914, when a discouraged Orville was preparing to sell the company; delays by legal maneuvering continued into the 1920s.

Orville sold the Wright Aircraft Company in 1915 and went home to a household run by his sister Katherine, built a laboratory close to the original bicycle shop and for the rest of his life worked there alone on any scientific research that took his fancy. He continued to advise others, among them his friend Charles Kettering, who partnered in creating the Dayton-Wright Airplane Company in 1917, just as The United States was entering World War I.

The Brothers' Legacy

Orville's father Milton died in 1917, and in 1926, Katherine—much to Orville's dismay—married and moved to Kansas City. Orville was persuaded to reconcile with Katherine just before her death in 1929.

Orville continued in public life, promoting aeronautic development and invention and protecting the Wright Brothers' legacy. This included an ongoing argument with the Smithsonian Institute which had clearly discounted the Wrights' original contribution to airplane development, prompting Orville to donate the 1903 Wright Flyer to the Science Museum in London. Only in 1948, after the Smithsonian conceded the Wrights' precedence, was the airplane returned for display in the United States.

Orville Wright died of a heart attack in Dayton, Ohio, on January 30, 1948, at the age of 76.

Methodical Steps

Orville Wright applied the Scientific Method to his work from the beginning of his fascination with aviation through its culmination at Kitty Hawk on December 17, 1903.

He followed the methodical steps of researching information from reliable sources: defining the problem to be solved, proposing a solution or hypothesis, designing meticulous experiments to test the hypothesis and perform the testing, and finally, after repeated redesign and retesting, solving the problem. As engineers, the Wrights were more interested in building working machines than in discovering enduring scientific truths. Their efforts with bicycles, kites, gliders, and airplanes fulfilled both.

Gathering Information

Beginning in 1896, the Wrights progressed from information in their father's library and the local public library to requesting information from the Smithsonian Institution. Their information base grew larger as they gathered books describing the birth of aviation by authors such as Chanute, Lilienthal, and Langley.

Using this information, the Wrights first flying machine was a kite, built in 1899, which incorporated their essential solution to the question of directional control during flight. With sticks attached to lines connected to the edges of the kite's wings, the operator was able to bend or twist the leading edges of the wings to cause dipping and lifting. Dipping at one side made the kite turn in the dip direction and lifting across the front caused the kite to fly upward (reversing the direction caused downward flying). Most importantly, reliable flight control was achieved.

Testing

In 1901, the brothers saw the first somewhat disappointing trip from Ohio to Kitty Hawk, North Carolina, to test the first Wright glider in high wind conditions. While bad weather and shortage of materials dogged the task, the brothers were able to collect enough information to take back to Dayton for examination and further inspiration. They began to doubt the accuracy of Lilienthal's data and his calculated coefficients of lift and drag; the gliders they had built fell far short of the predicted performance.

On returning home, the brothers set out to painstakingly create their own data. From bicycle shop materials, the Wrights built a wind tunnel to measure the aerodynamic results of various scale-accurate miniature wing shapes they fabricated. A pine box with a fan attached at the end was the tunnel and the measuring balances and airfoil shapes in the tunnel were made from spoke wire and hacksaw blades. A completely controllable glider, designed and built from the new data and relying on wind for its movement, was successful at Kitty Hawk in the summer of 1902.

Breaking Barriers

Having solved the control issue, the Wrights turned to the project of adding power to their craft, enough to support the added weight of a pilot. The airplane they designed and took to Kitty Hawk in 1903 contained a lightweight gasoline engine. On December 17, this craft broke through the manned flight barrier—the first lasting, controlled flight by a powered airplane.

The next step was to turn this prototype into a practical, everyday reality. The Wrights built an airfield in Ohio and spent the next two years on test flights and progressive improvements in the aircraft's design. In 1905, they had a reliable aircraft ready for sale.

Influential Presence

Persuading customers to overcome their skepticism was difficult; the U.S. Army Signal Corps didn’t purchase an aircraft until 1908. By then, Orville Wright was flying demonstrations in France and finding interested European customers. With commercial success came competitors ready to copy the Wrights' designs, and much time was spent in protecting patents that the brothers had quietly and carefully assembled during their years of work in Ohio.

The aviation industry was slow to develop beyond daredevil exhibitions, and the lack of progress took a toll on the brothers. In 1912, Wilbur Wright died from typhoid and not long after, in 1916, Orville sold the Wright Company and turned back to experimentation and invention. For the next 36 years, he remained an influential presence in aviation matters and an avid supporter of a wide range of inventions and inventors.

Acknowledgement

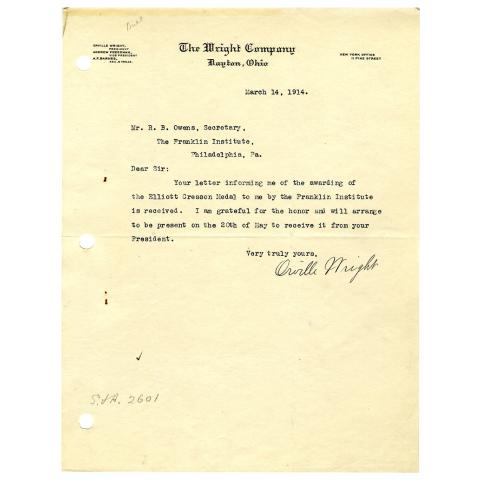

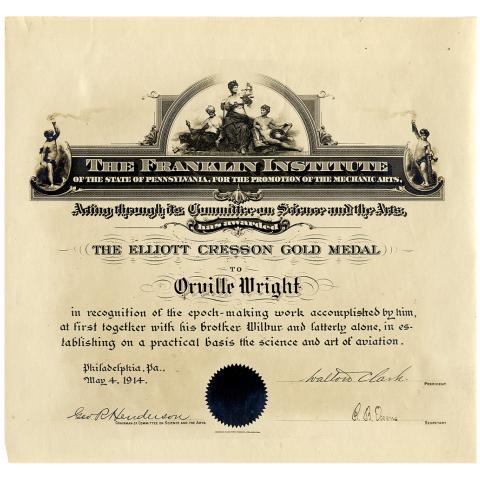

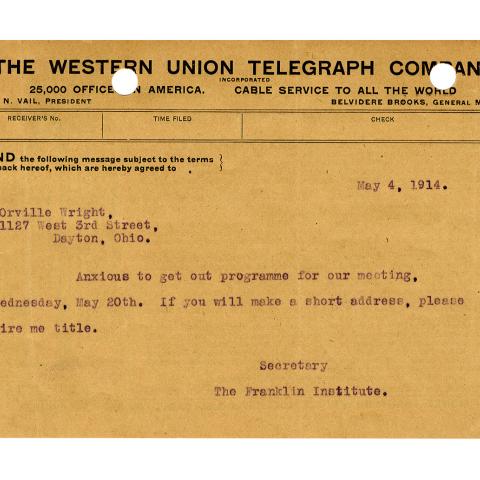

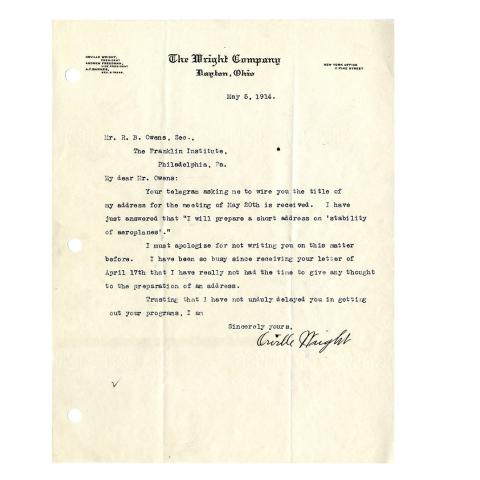

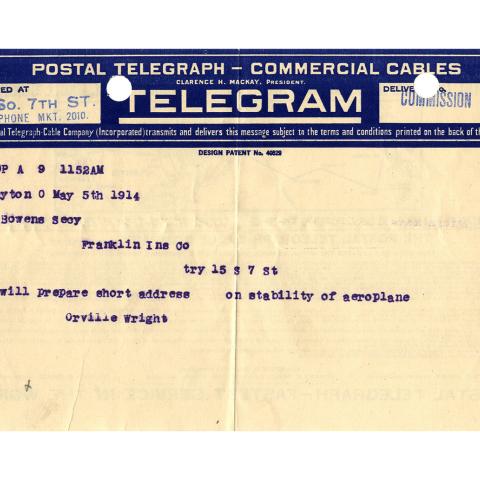

In 1914, Orville Wright was awarded the Elliott Cresson Gold Medal by The Franklin Institute "in recognition of the epoch-making work accomplished by him, at first together with his brother Wilbur and latterly alone, in establishing on a practical basis the science and art of aviation". Among the many other awards received by Orville Wright are:

- Numerous honorary degrees

- Gold Medals:

- The Aero Club of France, 1908

- The Aero Club of the United Kingdom, 1908

- Academy of Sports of France, 1908

- Aeronautical Society of Great Britain, 1908

- International Peace Society Medal, 1908

- United States Congressional Medal, 1909

- State of Ohio, 1909

- Aero Club of America, 1909

- French Academy of Sciences, 1909

- 1909 and 1924 Chevalier and Officer of the French Legion of Honor

- 1910 Langley Medal, Smithsonian Institution

- 1913 Collier Trophy, The Aero Club of America

- 1914 Elliot Cresson Medal, The Franklin Institute

- 1917 Albert Medal, Royal Society of Arts

- 1920 John Fritz Medal, American Association of Engineering Societies

- Bronze Medal, International Peace Society

- 1925 John Scott Medal, The Franklin Institute

- 1927 Washington Award, Western Society of Engineers

- February 1929, Distinguished Flying Cross, United States

- 1930 Daniel Guggenheim Medal

- 1930 Olympiad of the Air Medal

- 1932 Civitan Medal Badge

- 1933 Franklin Medal, The Franklin Institute

- 1936 National Academy of Sciences Membership

- 1948 U.S. President's Medal of Merit Decoration

- 1975 U.S. National Aviation Hall of Fame Medals

The Wright Brothers Medal was instituted in 1927 by the Society of Automotive Engineers and recognizes the author(s) of the best paper(s) relating to the invention, development, design, construction, or operation of an aircraft and/or spacecraft.

The Orville Wright presentation was made possible by support from The Barra Foundation and Unisys.

Read the Committee on Science and the Arts Report on Orville Wright’s work in the field of aviation.