Date:

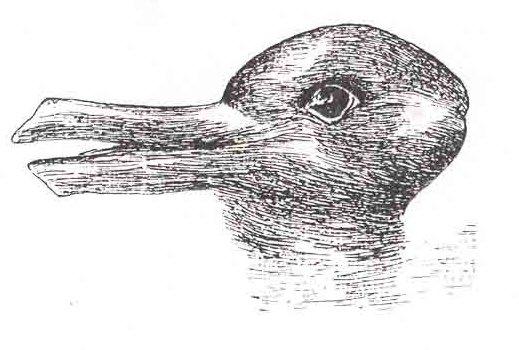

So, do you hear Yanny or Laurel? Is the dress blue and black or white and gold? Do you see a duck or a rabbit in the cartoon below? These phenomena are puzzling because they can be perceived in two very different ways. There's an explanation for the ambiguity in each one, whether it's audio quality, lighting, or facial features, but what fascinates me is our collective reaction to what they reveal about how our brains work.

The famous "duck-rabbit" illusion, originally noted by Joseph Jastrow, an American psychologist, in 1899. It was based on an earlier cartoon, by an unknown artist, published it in 1892.

The famous "duck-rabbit" illusion, originally noted by Joseph Jastrow, an American psychologist, in 1899. It was based on an earlier cartoon, by an unknown artist, published it in 1892.

To make sense of your world, sometimes your brain takes sensory information piece by piece to build up a picture of what’s happening. This is called "bottom-up processing." More often—as demonstrated by these phenomena—your brain operates in a "top-down" manner, making assumptions and predictions based on previous knowledge. (For another great example, try the "Say That Again" game in the Your Brain exhibit.) Top-down processing is much more efficient, but because each person's prior experiences are unique, it can lead people to perceive the same information in different ways.

It’s easy to assume that everyone sees the world the way that we do, so we’re shocked when we discover such disagreement over simple sensory information like the color of a dress or the sound of a word. But when it comes to our thoughts and beliefs, we see much more consequential impacts of differences in top-down processing. As I recently discussed with decision strategist and former world poker champion Annie Duke, cognitive biases that come from relying on our preconceptions can cloud our judgment, prevent us from hearing conflicting evidence, and lead us to irrational decisions.

Remember, however, that our brains are always changing—one study has estimated that the connections in our brain change approximately 13% every 100 days. While some of the brain’s expectations about the world may be so deep-seated that they are essentially hard wired, others are more flexible. Duke suggests that being aware of our cognitive biases can help us develop decision-making processes to overcome them. And if you hear “Yanny” today, be kind to those who voted for “Laurel.” Someday, that could include you.