Date:

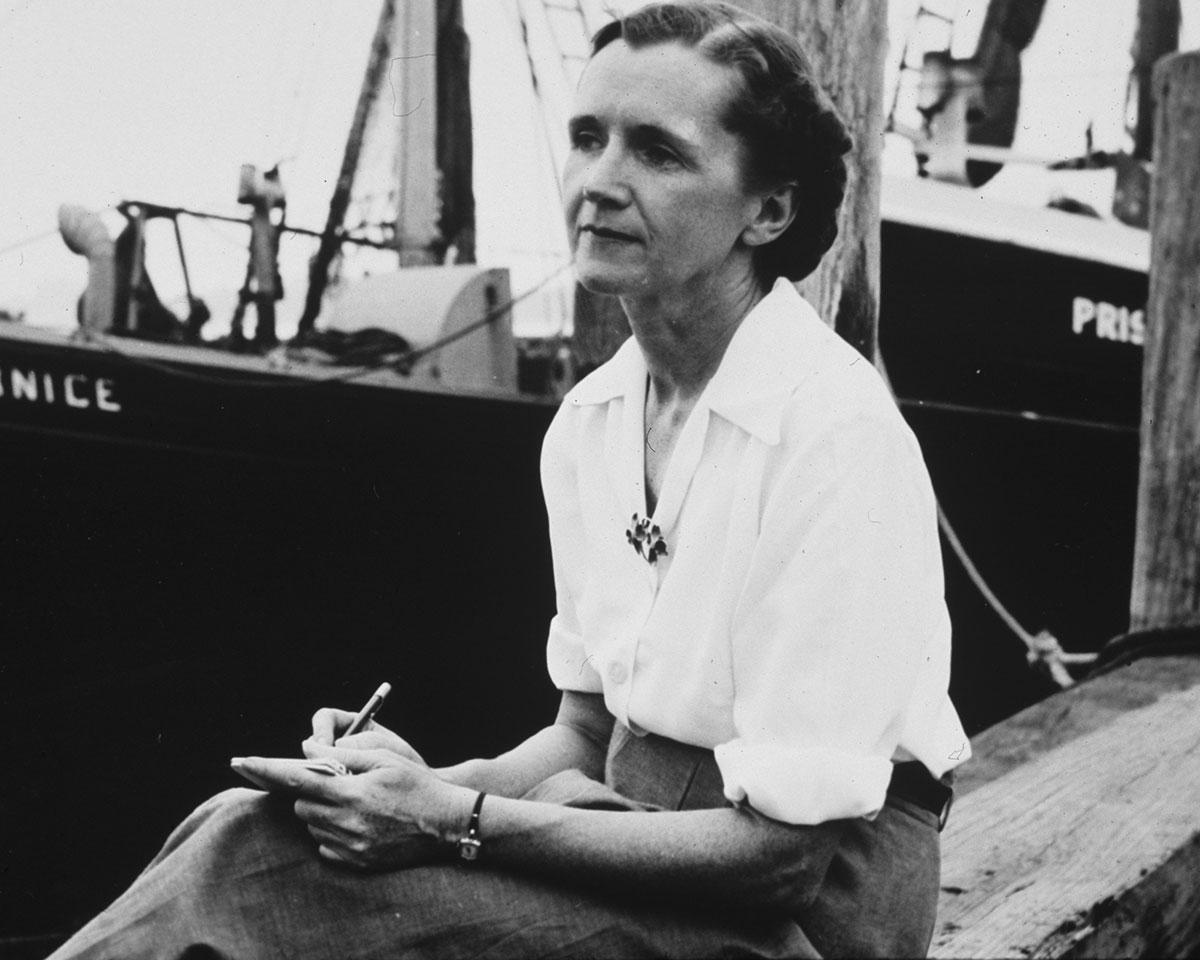

Editor's Note: Rachel Carson, marine biologist, author and environmentalist, was born on May 27, 1907 in Springdale, Pennsylvania. We asked The Franklin Institute's Environmental Scientist, Rachel Valletta, to blog about Carson's legacy and the ongoing importance of her work.

“She was not just a pioneer in the environmental movement… she pioneered it.”

Gina McCarthy, former Administrator of the Environmental Protection Agency, used these words to describe none other than Rachel Carson, the unassuming mother of the modern American environmentalist movement.

Perhaps we recall Carson best for her 1962 best-seller, Silent Spring, in which she documented the environmental impact of excessive pesticide use, especially DDT. Trained in biology, Carson was adept at the kind of long-term observation required to document shifts in the behavior and health of wildlife. She used her book, a masterful work of science communication, to deliver cutting-edge findings in a relatable fashion, and to challenge her readers in a deliberately provocative way. Consider her graphic account of an encounter with a poisoned squirrel:

The head and neck were outstretched, and the mouth often contained dirt, suggesting that the dying animal had been biting at the ground…. By acquiescing in an act that causes such suffering to a living creature, who among us is not diminished as a human being?

Her poignant and skillful writing was surpassed in passion only by her fierce moral commitment to her cause. At a time when humans saw their environment as something to be controlled, something to be conquered, Rachel Carson urged the public to understand that our health is delicately intertwined with the health of all the natural systems around us.

In this regard, Carson advocated for an entirely new way of thinking. She employed “systems thinking,” a way of approaching a problem from the whole, rather than its parts. For example, in considering the use of DDT as an insecticide, there are immediate, meaningful benefits in agriculture and human health -- killing off pests the threaten crop yields -- but there are also unintended environmental and ecological consequences that are both enduring and impactful -- like massive die-offs of fish and wildlife populations.

While others were only seeing the former, Carson used systems thinking to conceive of the entire picture. At a deeper level, Carson was acknowledging that humans are capable of profoundly altering the natural environment. (Sound familiar?)

Let us use the anniversary of her birth to honor Rachel Carson’s legacy and to reimagine once again our relationship with nature:

… [man] is himself part of nature, subject to the same cosmic forces that control all other life. Man's future welfare and probably even his survival depend upon his learning to live in harmony, rather than in combat, with these forces.

-Rachel Carson, "Essay on the Biological Sciences" in Good Reading (1958)