Date:

Written in partnership with The Jefferson Health Design Lab.

3D printing has become a hot topic over the last two years as rapid manufacturing has addressed some of the supply shortages experienced during the COVID-19 pandemic. However, there is more room for 3D printing in healthcare beyond masks, face shields, and ventilator parts.

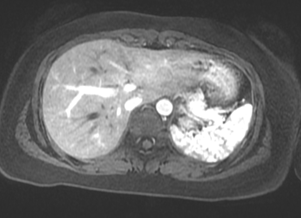

When being seen in a hospital or an emergency room, it is not uncommon for patients to get imaging done; this might be an X-Ray, CT scan, or MRI, each a different method of taking pictures to see inside the body. Physicians go to school for years to learn how to interpret these pictures to make diagnoses, so, understandably, these images look like a black-and-white abstract painting to most people. So how do we navigate this barrier, knowing that images are a powerful educational tool, when discussing illness and treatments? Well, one way is to convert the images back into a 3D structure.

At the Jefferson Health Design Lab, medical images are used to create digital 3D models and then take it one step further and print out the anatomy of interest using different kinds of 3D printers. By printing out a person’s own organs, the patient and their doctor can now discuss their diagnosis and treatment in a way both parties can easily understand. Creating these individualized and true-to-life scale models helps bring out better questions, improve understanding of a complex procedure, and encourage patients to feel more in control of their own care.

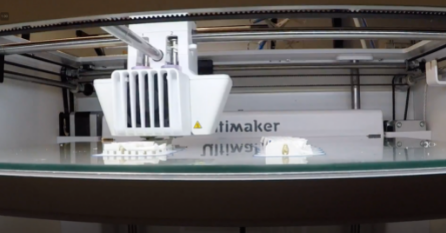

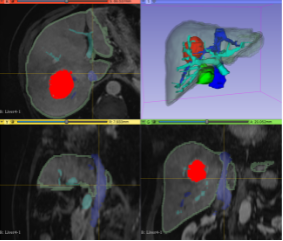

Making the models is a multi-step process; it begins when a doctor orders a medical imaging scan. The patient visits the radiology department for their scan, and X-ray technicians take a lot of images in sequence, moving across a section of the patient's body. For certain procedures, such as surgery to remove cancer, the Health Design Lab team can take those same imaging slices and create a digital 3D rendering. This is done by coloring in the desired areas on each 2D image, slice by slice, and using special software to turn this into a new three-dimensional file (a 3D rendering). This rendering is an exact 3D replica of the anatomy that is important in each patient’s case.

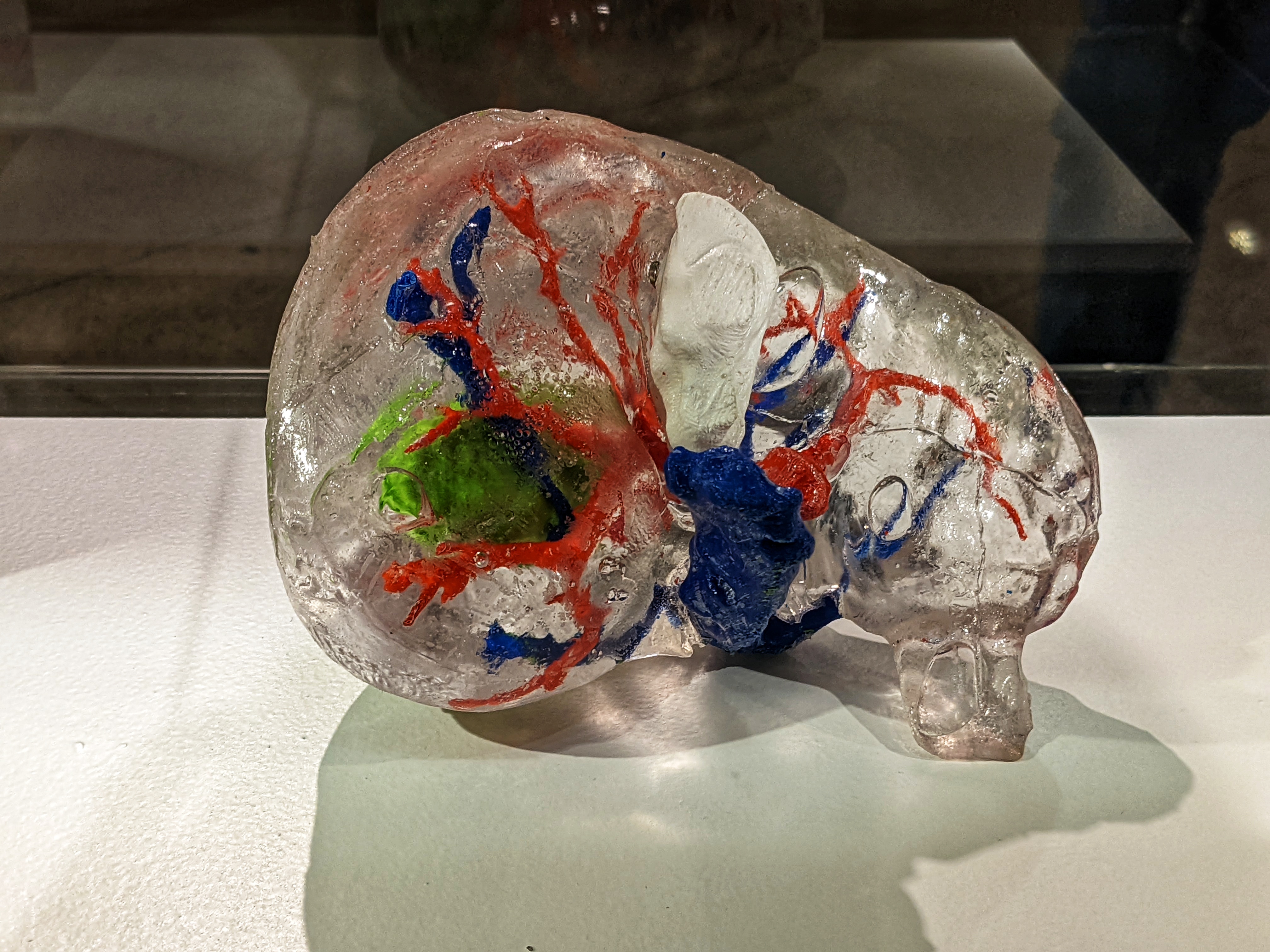

This digital rendering is then prepared into a format that a 3D printer can read, keeping into consideration things like the color of the material and the size of the model. Using the 3D information we send it, the printer builds up the model layer by layer. Now, a real organ--first fully digitized--exists as an almost exact plastic replica back in the real world. When printing different organs, various colored plastics can be used together to make a more complex model. If surgery is needed to remove a tumor, it can be printed using a different color than the organ it is growing in, so it is easier to see on the final model.

An example is currently on display in The Franklin Institute's Tech Studio: a model of hepatocellular carcinoma, a common liver tumor that a patient needed to have surgically removed. During the surgery, a section of the liver surrounding it also needs to be removed, along with other nearby organs blocking the surgeons' way. It is hard to appreciate this on a CT or MRI scan because the tumor in the liver is about three computer mouse scrolls away from a nearby organ, the gallbladder, that sits in front of it, so they don't appear on the 2D image. This causes confusion, as patients don't often understand why removing the gallbladder is necessary if the tumor is in the liver. However, when holding the 3D model in their hands, they see clearly that the neighboring organ also needs to come out to remove the tumor.

3D printing helps to empower patients and can have many other valuable and long-lasting impacts on healthcare. The Jefferson Health Design Lab is actively researching the benefits of 3D printing in medical education, reducing healthcare costs, and improving surgical outcomes.

For more information about 3D printing in the medical field, specifically about using organic tissues (bioprinting), listen to Season 1, Episode 10 of The Franklin Institute’s podcast, So Curious!