Introduction

Who was Elmer Ambrose Sperry? What was the Searchlight?

How did the Sperry Electric Company begin? What is the legacy of Sperry, his science, and his rewards?

A Nation in Need

World War I brought innovation in gas, tank, aerial, and submarine warfare. The success of the Sperry gyrocompass responded to the needs of submarine warfare, aiding the navy's stealthy undersea behemoths in keeping their courses and accurately firing their weapons. The development of night flying resulted in night attacks, which created a need for improved defense searchlights.

Sperry and his company responded to a call for improved defense against aerial attack with their high intensity searchlight. This searchlight was developed between 1914 and 1916, and considered for award by the Franklin Institute's Committee on Science and the Arts starting in 1917. Due to wartime pressures and to complications with the U.S. Patent Office encountered by Sperry, the evaluation of the invention did not take place until 1920. An examination of the Sperry case file reveals that Sperry's company was hesitant when providing the Franklin Institute with documents for perusal by the Committee on Science and the Arts, due to the ongoing war and the need for national security.

Sparking an Interest

Inventor Elmer Ambrose Sperry dabbled in various scientific fields on his quest to improve technology. In 1880, twenty-year old Sperry had just completed his studies at the Cortland Normal school of New York's Cortland village. The young man focused his scientific interests on electricity. This interest was sparked by the publicity given to Thomas Edison's invention of a practical incandescent bulb during Sperry's final term at Cortland Normal. Sperry was also interested by the arc lamp, developed by Charles Brush of Cleveland, Ohio, which had been famous for several years prior to Sperry's graduation. The late 19th Century, saw the novel world of electrical engineering open wide to the technological possibilities dreamed up by bright young inventors.

Company History

Sperry founded his first company in 1880 in Chicago. The Sperry Electric Company manufactured the electric dynamos and arc lamps that Sperry had invented as a teenager. Over the next fifty years, Sperry's staggering number of inventions prompted him to found seven more companies for the sale and manufacture of his novel devices. Among these were Sperry Electric Mining Machine Company, Sperry Electric Railway Company, Chicago Fuse Wire Company, and Sperry Gyroscope Company.

The war in Europe created a demand for gyrocompasses that contributed significantly to the growth of Sperry Gyroscope. The Allied navies turned to Sperry with their need to equip both surface ships and submarines with the compass. As a result of these sales, Sperry Gyroscope expanded its facilities, as well as its profit. All of Sperry's companies eventually evolved into the Sperry Corporation.

In 1955, Sperry Corporation acquired Remington Rand, an early American computer manufacturer. The company was briefly renamed "Sperry Rand," but in 1978 it decided to concentrate on its computing interests and reverted back to "Sperry Corporation." In 1986, Sperry Corporation merged with Burroughs Corporation to form Unisys Corporation.

Return of the (Scientific) Soldier

An arc light is a type of lamp that produces light when electric current flows across a gap between two electrodes. Sperry applied this principle in developing his own arc light, which he designed and built under the auspices of the Cortland Wagon Company, from 1880 until 1881. With the support of both the wagon company's funds and its engineers, Sperry developed a complete arc light system between the summer of 1880 and the fall of 1882. His work would veer away from electricity in the ensuing years, but Sperry returned to the field in 1914, as the American nation stood on the verge of war.

The U.S. Navy saw a need for a high-intensity searchlight in the early 20th Century, recognizing that the range of existing searchlights was exceeded by that of improved guns. Desirous of eliminating this discrepancy, the navy became interested in the high-intensity searchlight developed by Heinrich Beck. At the time, Beck held the position of manager of the Physikalisch-technisches Laboratorium in Germany. Beck's searchlight boasted a more concentrated beam, and an illuminative capacity five times the standard navy searchlight. Impressed by the reputation of Beck's searchlight, the navy asked the German inventor to estimate the cost of converting existing lights to his design, and of installing new searchlights aboard naval ships. Beck would need to find American manufacturing facilities before he could consider the possibility of undertaking this task, and so Sperry's name was brought into the picture. Beck asked $100,000 for the patent rights to American manufacture and sale.

Seeing the Light

Sperry's own experience working with arc lights convinced him that the Beck design wanted improvement, and he was not under the impression that Beck's patent protected his lamp against imitation or competition. Having encountered resistance from Sperry, Beck sold his patents to General Electric for $135,000, and General Electric in turn supplied the navy with the Beck high-intensity light.

Sperry responded to this business transaction by investing in the development of his own version of the high-intensity lamp. Sperry informed the navy of his plans for improving the Beck searchlight in 1914. The cunning inventor proposed to do away with the alcohol vapor with which Beck surrounded and cooled the arc lamp, to simplify the automatic mechanisms in the searchlight, and to opt for the use of pure carbon electrodes rather than impregnated carbon. Sperry worked closely with a new member of his staff, Preston Bassett, on the development of the searchlight.

A graduate of Amherst and a Chemistry major, Bassett's help proved invaluable. He worked closely with the National Carbon Company in Cleveland to develop improved carbon electrodes for the high-intensity light, and designed a positive electrode that would render the light more powerful. The chemistry and design of the carbons and the positioning of the positive and negative electrodes in Sperry's lamp set his design apart from Beck's. Different, too, was Sperry's method of cooling the electrodes and thus restricting the flow of current in his lamp. Beck used alcohol vapor to accomplish cooling, but Sperry deemed his apparatus for generating the alcohol fumes and directing them to the electrodes clumsy. Sperry and Bassett therefore resorted to air cooling.

Losing No Time

After tackling the task of improving the arc light, Sperry and Bassett began designing the complete searchlight. The inventive pair came up with ingenious ways to ventilate the searchlight housing, known as a drum, to cool, automatically feed, and rotate the electrodes, and to automatically position the positive electrode crater so that it was at the focal point of the reflector mirror. The formation of a deep crater in the positive electrode had been a development of Bassett's. He had achieved this by designing a positive electrode that was composed of two parts: a shell and a core. The material he chose for the core burned faster than that of the shell, enabling the burning core to recess into the shell and form a deep crater in the positive electrode. The arc flame and luminescent gases were confined in this crater, and the concentration of flame and luminescence in the crater resulted in the intensity of the searchlight.

Mission Accomplished

In 1916 Sperry began marketing his high-intensity searchlight. In competitive tests held by the Army Coast Artillery Board, Sperry's searchlight was found to be superior in twelve of the thirteen tests. These tests measured light intensity, target illustration, simplicity of operation, and reliability. Only in carbon consumption were the Beck and Sperry searchlights scored equally. On the recommendation of the Army Coast Artillery Board, the army awarded the Sperry Company a contract for converting coast-defense searchlights to the Sperry system. The company triumphantly took on this task, which kept its employees busy for over a year.

While Sperry was successful in his dealings with the U.S. Army, consideration of the case being built for his high intensity searchlight was tabled and ultimately thrown out by the Franklin Institute. Work on the case was laid aside due to controversy over patents, and litigations brought against Sperry Company by General Electric, the owner of Beck's patent. Due to the persistence of this disruption, case #2710, "Sperry High Intensity Searchlight," was abandoned by the Committee on Science and the Arts in April of 1920. Letters dating back to 1921 indicate that the file was opened again at this time, but no further documentation attesting to the ultimate fate of the case has remained on file. The opinion of the Committee on Science and the Arts on the originality and effectiveness of the Sperry high intensity searchlight thus remains a mystery.

The images on this page link to the text of the report compiled by the Committee on Science and the Arts on Sperry's Searchlight in March, 1918.

Open-Type Searchlight Booklet

Page through the original Open-Type Searchlight booklet on this page.

Click on the right-hand page, drag it to the left, and click to drop the "turned" page. View successive pages of the booklet in this way. To magnify details of a particular page, click the Magnify tool at the bottom. Close it by clicking the "X" on the Magnify tool.

For optimal viewing, you may want to launch and maximize another window. Be sure to close the window in order to return to this exhibition. The Searchlight Instructions and Part List Manual is also available.

Searchlight Instructions and Part List

|

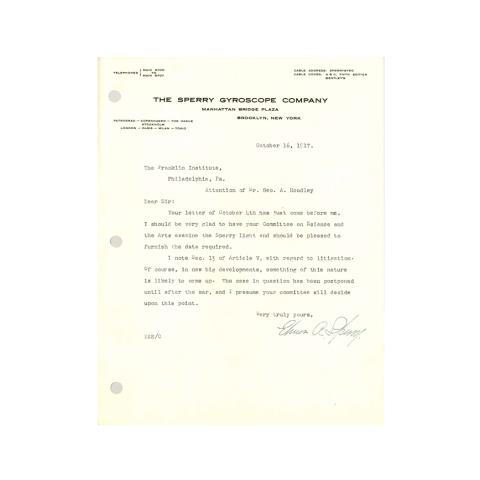

The letter above was sent by the Sperry Gyroscope Company's attorney, Herbert H. Thompson, to acting Franklin Institute secretary George A. Hoadley, indicating that the accompanying instruction manual for the Sperry searchlight (below) should be kept confidential due to the war. |

Page through the original Searchlight Instructions and Part List manual on this page.

Click on the right-hand page, drag it to the left, and click to drop the "turned" page. View successive pages of the booklet in this way. To magnify details of a particular page, click the Magnify tool at the bottom. Close it by clicking the "X" on the Magnify tool.

For optimal viewing, you may want to launch and maximize another window. Be sure to close the window in order to return to this exhibition. The Open-Type Searchlight Booklet is also available.

Mission Accomplished (continued)

January 11 & 12, 1921: The suit brought against Sperry by General Electric was settled, clearing the way for the searchlight case to be reopened for evaluation.

January 19 & 22, 1921: The Franklin Institute questions the originality of Sperry's high intensity searchlight, and Thompson heartily defends.

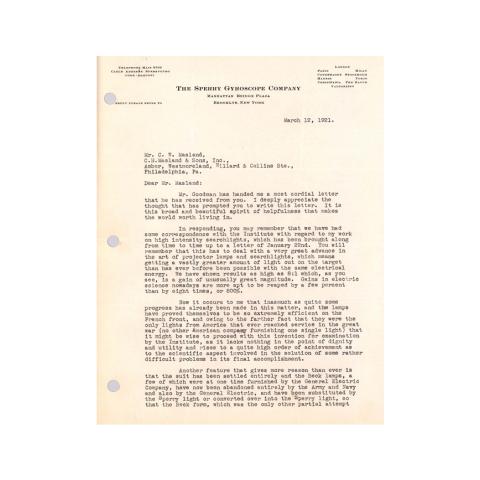

March 12 & 15, 1921: These letters, the most recent documents in the case file, were sent between Sperry and CSA member C.W. Masland, in what appears to be the final days of the Committee's evaluation of the Sperry searchlight. Sperry describes some of the outstanding features of his machine, and Masland passes the inventor's letter along to the Committee. These two letters indicate that the evaluation was indeed started up again in 1921, but no further information on the case exists.

The Elmer A. Sperry presentation was made possible by support from The Barra Foundation and Unisys.

Read the Committee on Science and the Arts Report on Elmer A. Sperry’s High-Intensity Search-Light.