Introduction

As a woman born in 1867 Poland, Marie Sklodowska Curie had a steep hill to climb in her pursuit of her passion for science. She stands among the greatest scientists of all time, male or female. Certainly, she stands tallest as a role model for generations of young women who followed in her footsteps, pursuing careers in scientific research.

Who was Marie Curie? How did she come to be a scientist? What important work led to the discovery of radium?

In Search of Education

Maria Sklodowska was born on November 7, 1867, in Warsaw, Poland, which was then part of the Russian Empire. The Polish nationalist sympathies of Maria's parents resulted in employment difficulties for her father, a teacher, causing the family of seven financial troubles.

Maria completed her high school studies in the state system by the age of 15, but then experienced a setback because the University of Warsaw did not admit women. Instead, Maria and her older sister, Bronya, joined a group of students in clandestine studies in which each student shared their specialty with the others.

It became obvious that further education would only be available elsewhere in Europe and the sisters agreed that Maria would find work and income to support Bronya, who moved to Paris to study medicine. During the next five years Maria worked as a private teacher and then as a governess while contributing to Bronya's benefit. With time available in her isolated working location, Maria continued to study a variety of topics, eventually settling on physics and mathematics as her favorites. Through the help of a cousin, Maria found instruction in chemistry together with some practical laboratory experience. A good turn in her father's finances made it possible for Maria to move to Paris, and so in the fall of 1891 at the age of 24, she enrolled at the Sorbonne.

A Partnership

Enduring the hardships of student life on a tight budget and the challenges of catching up to acceptable levels in her chosen subjects required all of Maria's energy, yet in two years she had master’s degrees in mathematics and physics, scholarship recognition, and research projects to accomplish.

Maria's research required laboratory space and a scientist friend suggested that his French colleague, Pierre Curie—also researching magnetism—could help provide some space. So began the partnership that led to outstanding landmarks in the progress of physical science.

Drawn close by their work, Pierre and Maria (now called Marie in France) were married in June, 1895. In the same year, Pierre's long-time research was rewarded with a doctorate and a professorship.

Elemental Discovery

By the time their first daughter, Irene, was born in 1897, Marie had her teaching diploma and resolved to go on studying for a doctorate. As a thesis topic, she chose to further investigate the "uranium rays" that Henri Becquerel had reported on just a year earlier.

First, Marie Curie used a methodical approach to determine which elements emitted this radiation; the results indicated uranium and thorium to be the only candidates. Minerals and ores which contain these elements were her next targets. After exhaustive investigation, using the mineral pitchblende as starting material, the new elements polonium and radium were detected. This work was reported in December of 1898.

Marie and Pierre continued to teach and pursue their research in grim conditions; a large, unheated shed served as the laboratory in which they prepared a decigram sample of very pure radium chloride. This effort culminated in Marie's doctoral thesis, which she submitted in 1903. The doctorate was awarded amid general acclaim concerning the scientific value of this breakthrough.

While awed by their discovery, the Curies did not realize the unfavorable medical consequences of the glowing radiation from the small samples they constantly handled. They were frequently tired, the skin of their fingers was scarred and cracked, and illnesses beset them.

Interested in learning more about Marie Curie? Learn More About Her Cresson Award

Triumph and Tragedy

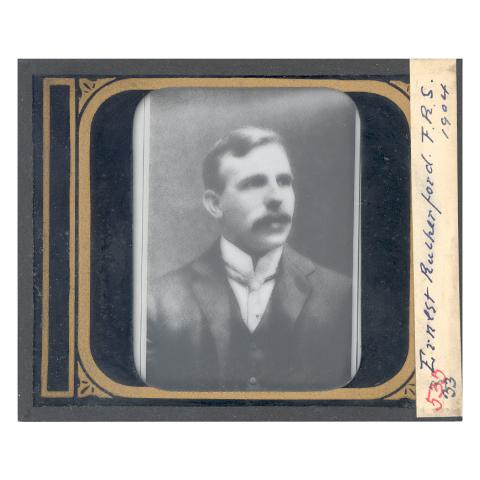

In 1903, the third Nobel Prize in Physics was awarded to Henri Becquerel, Pierre Curie, and Marie Curie for their work on the radiation of uranium. Illness prevented them from accepting the prize until 1905.

This date marked the beginning of the life of the Curies as celebrities; their preferred privacy was over. Then, a year later, on April 19, 1906, tragedy struck. Pierre Curie was run over by a horse-drawn cart while crossing the street and killed, leaving Marie with two daughters, Irene and the two-year-old Eve.

With typical strength and commitment, Marie gathered herself together to succeed Pierre as head of the laboratory, becoming the first woman to teach at the Sorbonne. Building on her own experience, Marie developed a unique educational situation for Irene. The children of the Sorbonne faculty were taught by their parents in a variety of subjects in completely non-traditional fashion. An emphasis on science and mathematics was included.

A full professorship, again the first to a woman, was awarded to Marie Curie in 1908. She went on to be the sole recipient of the 1911 Nobel Prize in Chemistry for her discovery of radium and polonium and subsequent research on their properties.

During the next two years, Marie's life became chaotic involving scandal, media persecution, and collapse from ill health. The scandal involved a relationship with a married student, Paul Longevin, which led to highly critical scrutiny from the French press. Following this stressful time, Marie spent 1912 being treated for physical ailments and depression, then recuperating in England and France.

Reviving in 1913 to return to the Radium Institute, Marie's work was next interrupted by the outbreak of World War I. Newly energized, she worked with her daughter, Irene, to ease the pain of wounded soldiers by creating and organizing mobile X-ray stations and implementing medical applications of radium in destroying infection.

When peace returned, Marie Curie devoted her efforts to extending the work of the Radium Institute by seeking funding sources in Europe and, more successfully, in the United States. Even though her health was failing, she traveled extensively and was welcomed everywhere as a celebrity advancing the knowledge and popularity of science.

The Radium Institute, now renamed the Curie Institute, was operated by Irene Curie and her husband, Frederic Joliet. They in turn received the 1935 Nobel Prize in Chemistry for advances in nuclear research.

Marie Curie died at the age of 67 on July 4, 1934 of leukemia, which may have been caused by her lifetime exposure to ionizing radiation. Her papers from the 1890s are still contaminated with radiation, and researchers must wear protective clothing before removing them from the lead-lined boxes which contain them.

Research Focus

Marie's early research in Paris centered on correlating the chemical compositions of various steels with their magnetic properties. An important consequence of this work was her meeting with Pierre Curie, himself a long-time researcher on magnetism.

After publishing the results of her research, Marie turned to considering topics for her doctoral research. Following the recent work of Henri Becquerel, who reported on the spontaneous radiation emitted by uranium compounds, Marie Curie decided to focus her research on further investigation of this new phenomenon.

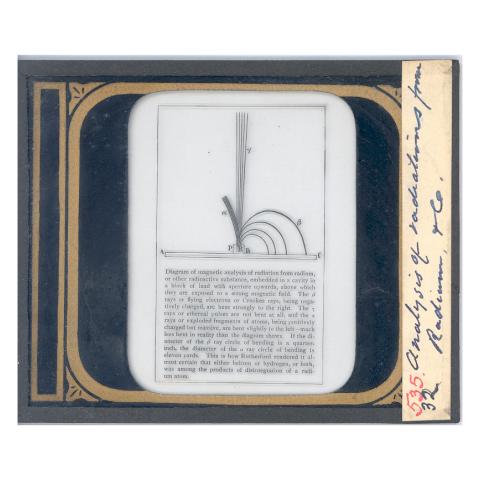

To measure the weak electric currents caused by the radiation and obtain comparable data, Curie used the electrometer invented by her husband, Pierre, and his brother, Jacques, rather than rely photographic plate intensities. The emissions were found to be constant and independent of physical state or purity; radiation strength depended only on the amount of uranium in the sample. This led to Marie Curie's first hypothesis that the radiation originated in the elemental uranium in the sample.

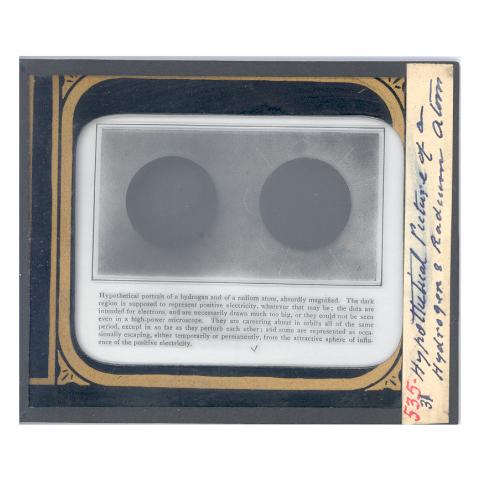

This fundamental observation set the stage for subsequent discoveries on atomic structure and the intrinsic power of the atom. Whereas up to that time the atom was considered to be the smallest, indivisible particle existing in matter, the radiation observed would indicate that the "indivisible" atom was now subject to decomposition to smaller components.

Polonium and Radium

Curie now expanded her search for other "Becquerel-ray emitting" compounds using pitchblende from Joachimsthal, Austria, and found the element thorium to have the same emission characteristics as uranium. She coined the term "radioactivity" to describe this property. Her next hypothesis—that certain complex materials, such as pitchblende, achieved their high radioactivity from the presence of additional as yet unknown elements—then required to be tested by isolating such elements.

Pierre Curie joined Marie in the next stage of the task where various chemical extraction techniques were used to separate the components of pitchblende. His electrometer was again used to measure radioactivity in the resulting fractions. From this work, in 1898, the Curies reported the existence of two new, separate elements that they named polonium and radium.

A Pure Compound

The next step, isolating pure compounds of the new elements, proved next to impossible. While radium chloride was obtained by repeated re-crystallization, it was not possible, despite a beginning sample of 50 kilograms, to isolate a pure polonium compound.

All attention was now centered on radium. A large-scale extraction in 1910 yielded sufficient amounts and led to isolation of radium metal and detailed examination of the element's properties. The atomic weight was found to be 225. Its radioactive power is at least a million times greater than that of uranium, penetrating thick photographic plates. Radium is spontaneously and continuously luminous and heat producing.

Radium was used in medicine to destroy cancerous tumors by implantation of a radium source directly in the tumor. It increasingly came to be regarded as an elixir and restorative, but consequential, toxic side effects became known. The health hazard, termed "radiation sickness," caused such treatments to be discontinued in the 1930s and safer substitutes such as cobalt-60 came into use.

Acknowledgement

After the 1903 Nobel Prize in Physics, but prior to the 1911 Nobel Prize in Chemistry, Marie Curie was honored with a Cresson Medal by The Franklin Institute

The 1909 medal was awarded to Marie and her husband Pierre (posthumously), and was given in the field of chemistry for the discovery of radium. The Cresson Medal was awarded a year after Marie was granted full professorship at the Sorbonne.

The Franklin Institute Committee on Science and the Arts report for case #2413 follows. The Curie report is dated January 6, 1909.

The Marie Curie presentation was made possible by support from The Barra Foundation and Unisys.

Read the Committee on Science and the Arts Report on Marie Curie and her work in the field of chemistry.