Introduction

Igor Sikorsky was an important part of aviation history, from the flight of Wright brothers to the exploration of space.

Who was Sikorsky, and what were some of the advances he made in the field of aviation? What physics principles are required to make a vertical take-off and landing craft—a helicopter—work?

Scientific Interest

Igor Ivanovich Sikorsky was born on May 25, 1889, in Kiev, Russia. The youngest of five children (three daughters and two sons) of a psychology professor, he received his early education and a liking for the work of Da Vinci and Jules Verne from his mother, who was also a trained physician.

During a 1900 vacation with his father to Germany, the young Sikorsky developed an interest in the sciences, inspired by the news of aviation firsts to build a rubber-band powered helicopter model that lifted off the ground.

Back in Russia, at the age of 14, he moved into the Petrograd Naval Academy but left in 1906 to study engineering in Paris while revolutionary unrest was stirring in Russia. Back home, following a year in Paris, Sikorsky entered the Polytechnic Institute of Kiev.

Another trip to Germany in 1908 secured his interest in aeronautics, as the achievements of the Wright brothers and the flights of von Zeppelin's dirigibles were becoming known. Sikorsky interrupted his studies for another trip to Paris where he learned from leading aviators and purchased equipment for his experiments. He was determined to attempt aircraft design and follow his own determination to build helicopters.

Grounded

Returning to Russia with plans and a 25-horsepower engine, Sikorsky built a helicopter which met all dynamic and control principles, yet failed the crucial test: it could not lift off the ground. The weight of the required engine driving power overcame its lifting power. The helicopter project was cancelled, all useful data was recorded, and attention moved to fixed wing aircraft. The data was useful many years later when lightweight engines became available, reigniting Sikorsky’s passion to build helicopters.

Le Grand

In June of 1910, Sikorsky successfully flew his first airplane, the S-2. During the next few years, increasingly powerful designs were built and Sikorsky was issued a pilot's license by the Russian Imperial Aero Club. His S-5 model was a landmark in 1911, flying a circular course for four minutes. By 1912, the S-8 model had been created and a variety of airplanes were being sold to the Russian army. At that point, Sikorsky was already thinking of his next innovation: passenger air travel.

Now working with the Russian Baltic Railroad Car Factory, he built and flew the world's first four-engine airplane, the "Le Grand," in May 1913. Indeed "grand," this well-appointed aircraft weighed about 4500 pounds, had a 92 feet wingspan, and four 100-horsepower engines. An outside balcony permitted any of the four passengers to take an airy stroll; the passenger cabin boasted seats, a couch, and a washroom, and the pilots' cabin had two seats and dual controls. On June 18, 1914, a successor to Le Grand, the "Ilia Mourometz", set a world record by carrying eight passengers aloft for an hour and 54 minutes.

Military Mission

Soon enough, precipitated by the June 28 assassination in Sarajevo, World War I began and Sikorsky's company went into production to manufacture military versions of the Ilia Mourometz for use in reconnaissance and bombing missions. Three years later, the Bolshevik revolution shook Russia and, with reason to believe that his fame and standing made him a target, Sikorsky fled to France. His daughter from a short-lived marriage, Tania, remained in Russia. In 1918, the war ended and the market for a military airplanes dried up. Sikorsky, speaking of his admiration for Edison and Ford and the opportunities for success, left for America in March 1919.

Success was not immediate; new airplanes were not being built while leftover military machines were available and government development funding had ceased. Sikorsky survived as a teacher to other Russian immigrants in New York and in 1923 his sisters arrived from Russia, bringing his six-year-old daughter Tania. One year later Sikorsky married a fellow immigrant, Elizabeth Sermion, and four sons—Sergei, Nikolai, Igor Jr., and George—were born to the family. A group of his immigrant friends gathered enough funds to establish the Sikorsky Aero Engineering Corporation on a chicken farm in Long Island. Its first product was the model S-29-A passenger aircraft which was met with some success. Sikorsky became a United States citizen in 1928.

Gaining Fame

In that era between 1910 and 1930, aviation advances were encouraged by hundreds of prizes offered for various accomplishments, the most famous being the Orteig prize for the first person to fly between Paris and New York non-stop. Sikorsky was among nine competitors for the prize. Funded by French aviator Renee Fonck, he modified his 16-passenger model S-35 by adding a third engine, larger wings, and increased fuel capacity. Fonck's attempt failed and all others were soundly defeated by Charles Lindbergh's famous flight in May 1927. The Lindbergh flight broke the barrier to trans-Atlantic air travel and commercial aviation soon became a reality, first in air mail transport and then in passenger travel.

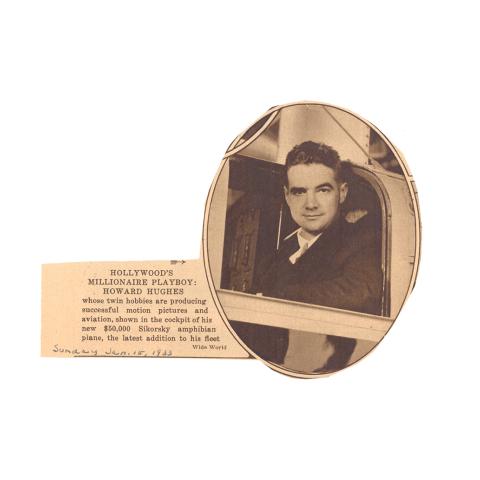

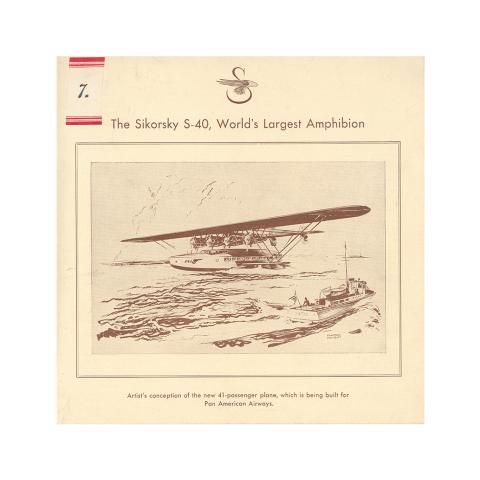

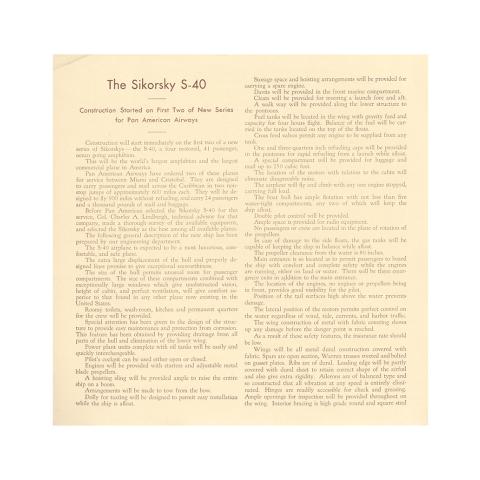

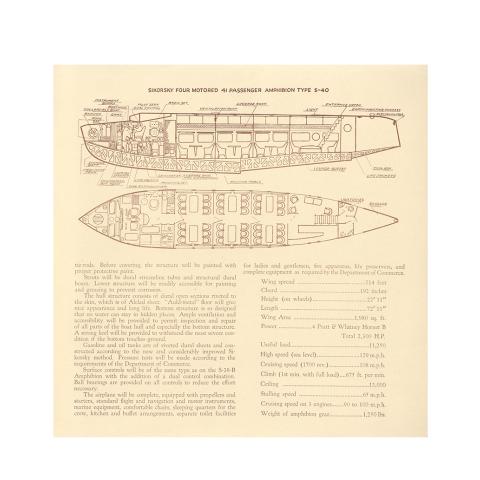

In 1929, the Sikorsky Aviation Company became a subsidiary of United Aircraft Corporation and partnered with Pan American Airways in building large capacity amphibious airplanes to service both domestic and foreign commercial routes, granting Sikorsky fame and recognition. The flying boats were christened "clippers" and traveled the world. In 1934, the S-42 flying boat was the first airplane to cross the Pacific Ocean. At that time, amphibians and flying boats were preferred for their ability to land on water in places where ground airports were not available. However, the age of the flying boats and their position as the flagships of passenger air travel was ending. Sikorsky Aviation's airplane production closed down in 1938, but Igor Sikorsky's role as an aviation pioneer was about to grow exceptionally.

Satisfaction

Igor Sikorsky continued working on helicopter design and production for the rest of his life, preferring to emphasize non-military applications and gaining most satisfaction from the unique suitability of helicopters to reach difficult areas on rescue and mercy missions.

Many awards were given to Igor Sikorsky from organizations such as the Aviation Hall of Fame, the National Economic Council, the National Academy of Engineering, the French Legion of Honor, the Royal Aeronautical Society, and the Russian Imperial Aero Club.

Following retirement in 1957, Sikorsky remained an advisor to the company, working there until his death at age 83 on October 26, 1972.

Rudders

In 1910, when Igor Sikorsky turned his attention from experimental helicopters to fixed-wing aircrafts, the airplanes in use were single-engined, unsafe for sustained use. Sikorsky's solution was to build multi-engined airplanes which would continue to fly in the event of an engine failure and would also be big and powerful enough to meet the goal of carrying passengers and freight over long distances.

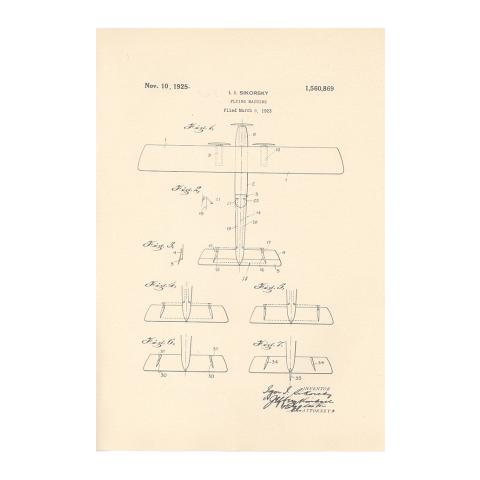

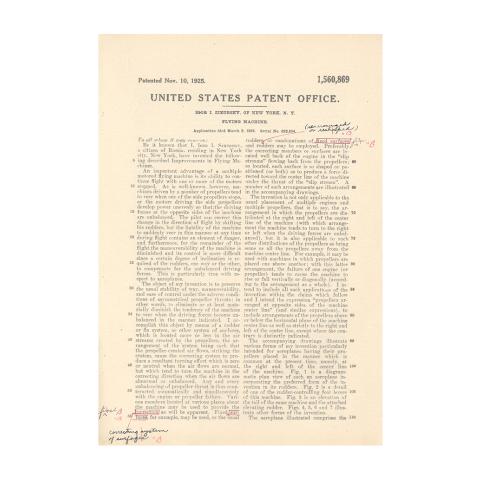

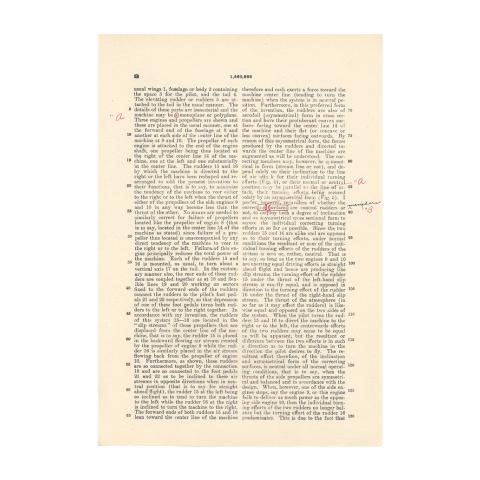

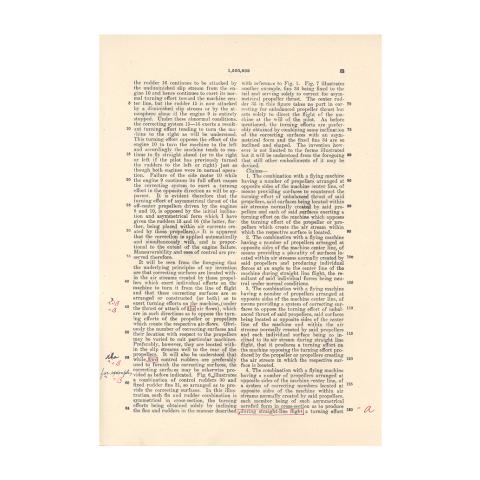

There were two crucial challenges: to create enough engine power to lift and carry the aircraft's weight plus its payload, and to maintain the pilot's control when an engine failed. The failure of an engine immediately disrupts the aircraft's balance and steering. Sikorsky invented an automatic control device that used tail wing rudders to restore directional control if an engine failed.

The rudders, operable by the pilot's foot pedal, are mounted vertically on the tail of the aircraft. In normal operation, the airstream effect across the rudders is zero and the pilot may use them for steering. On engine failure, the plane veers and the disturbed airstream across the rudders immediately and automatically stabilizes the aircraft.

Aircraft Models

Sikorsky named his developing aircraft models in a simple numerical series, S-1, S-2, S-3, etc., which represented all efforts—prototypes as well as models put into service. Those built in Russia from 1910 through 1916 were labeled S-1 through S-27G and his United States models were the series S-29A through S-44.

The S-21 Le Grand, or “Russian Knight”, his first multi-engined airplane, had a 90-foot wingspan, and four 100-horsepower engines to power its 7400-pound empty weight. It was the world's first successful four-engined airplane. This biplane, built mostly of wood, had a backup steering apparatus, top-wing ailerons for stability, and traveled at a maximum speed of 55 miles per hour. The final Russian model, the 27G with 880 horsepower, was the largest seaplane in the world.

In the United States, the S-29A, manufactured by the new Sikorsky Aero Engineering Corporation, was the first twin-engined aircraft able to fly on a single engine. Pioneering improvements followed as commercial air routes were introduced, and amphibian crafts, able to touch down on sea or land, were introduced. Sikorsky's final airplane design, the S-44, built in 1937, showed the longest travel range of any available commercial aircraft. The next Sikorsky models, the R-4 and its successors through the present, are helicopters.

Torque

High-power engines are necessary to drive rotating blades, which explains the delay in helicopter development after the Wright brothers' invention of the fixed-wing aircraft. The turboshaft engine, invented in the 1940s, matched the rotary wing power demands.

As the rotor creates lift, it also causes torque in the helicopter body attached to it. This torque will spin the body in the opposite direction to the rotary movement if left uncontrolled (Newton's law again). A small vertical propeller at the rear of the helicopter body, gear-connected to the main rotor, counteracts the torque force to keep the helicopter stable. In operation, the rear propeller will often overcompensate for torque and cause the machine to drift. Controlling the rear rotor (propeller) to compensate for the drift is one of the operator's tasks.

Level Flight

A helicopter's direction of movement is controlled by tilting the spinning rotor blades, the machine banking and rolling, moving in the direction of right or left tilt, and climbing or descending in the direction of an up or down tilt. Leveling the blades keeps the direction of movement to vertical only and power adjustment maintains a hovering position. Left or right turning is accomplished by altering the angle of the tail rotor which then acts like a rudder. The unique ability of a helicopter to fly backward is also controlled by tilt of the rotor blades.

The aim in flying a helicopter is to keep the power, controlled by the throttle, matching the requirements from directional movement of the machine, and avoiding engine stalling. Each alteration of main rotor pitch calls for matching power to those rotors to keep the system stable.

For straight, level flying, the helicopter pilot must add foot movement to the hand' movement already occupied with tilt and throttle. A pair of foot pedals operate the tail rotor pitch (or angle), turning the machine to the left or right and at the same time compensating for torque and drift.

Credits

The Igor Sikorsky presentation was made possible by support from The Barra Foundation and Unisys.

Read the Committee on Science and the Arts Report on Igor Sikorsky’s work in the development of multi-motored airplanes for different uses.