Introduction

"Equipped with his five senses, man explores the universe around him and calls the adventure Science." - Edwin Hubble

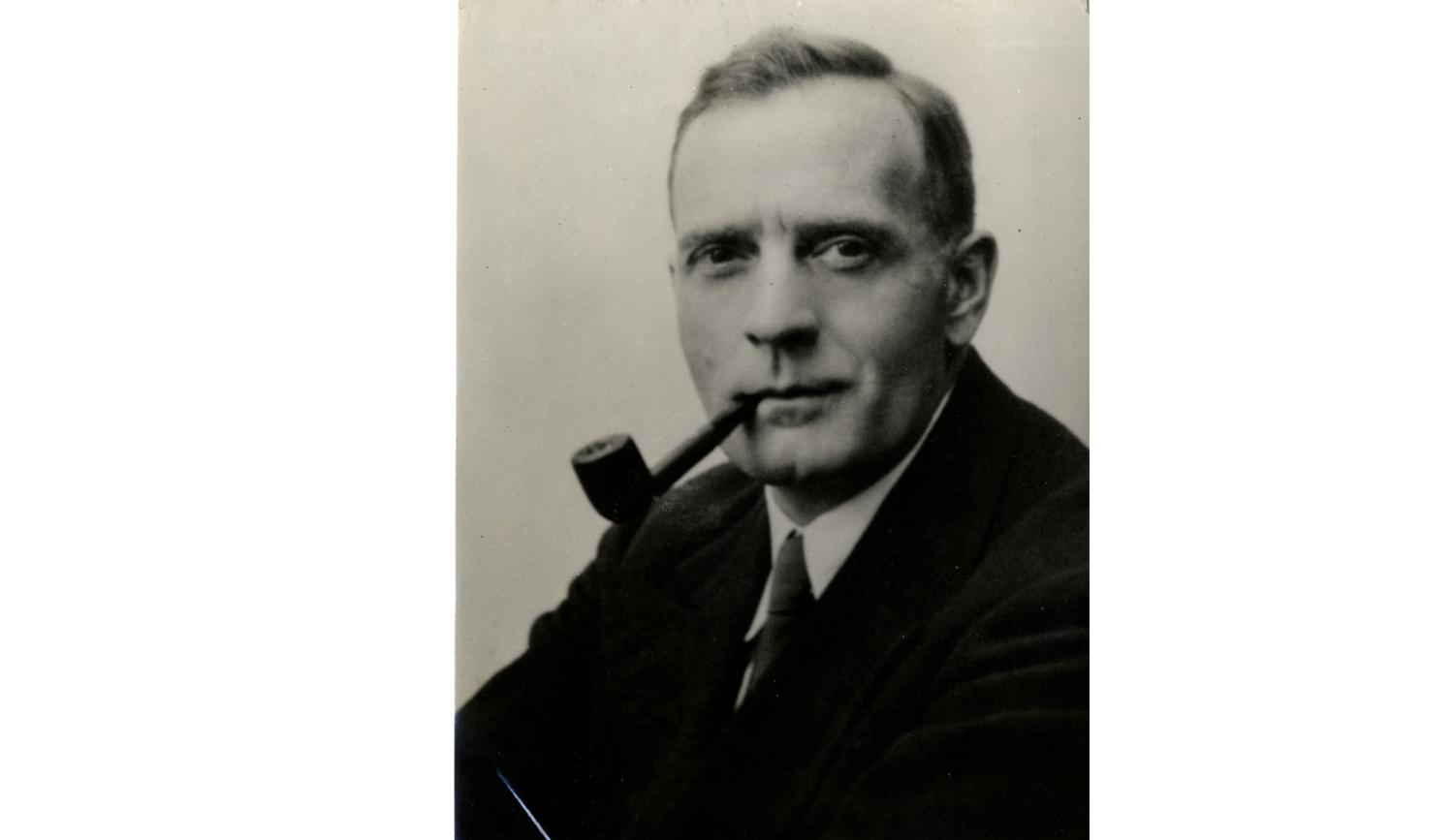

In the early 1920s, most astronomers believed that the Milky Way galaxy made up the whole of the cosmos. But Edwin Hubble changed everything when he came to the realization that the Milky Way is but one of millions of galaxies in a universe that is constantly expanding. In discovering the true nature of the cosmos, Hubble became the founder of observational cosmology.

Academics and Athletics

Edwin Powell Hubble was born in November of 1889 in Marshfield, Missouri to Virginia Lee James and John Powell Hubble. His father worked for an insurance company, and the family settled in Wheaton, a suburb of Chicago, when Edwin was nine years old. As a young boy, Hubble was an avid reader and became very interested in science. He was particularly close to his paternal grandfather, who once had an article written by the twelve-year-old Edwin published in a local newspaper. Interestingly, the article was about Mars.

Edwin excelled in academics and even more so in sports by the time he reached Wheaton High School. He was tall and strong, and quite skilled in basketball and boxing. Hubble also ran track, and set the 1906 high jump record for the state of Illinois.

A Promise

Hubble attended the University of Chicago, where he earned an undergraduate degree in astronomy and mathematics in 1910. He was awarded a Rhodes scholarship that same year, and traveled to England to study at Queen's College, Oxford. While there, Hubble continued to exercise his athletic abilities, but did not apply himself to the study of astronomy. It was a promise made to his dying father that saw Edwin instead pursuing law, while also studying literature and Spanish. He received his law degree in 1912.

Back to Science

In 1913, Edwin came home to the U.S. and was admitted to the bar. He set up a small law practice in Louisville, Kentucky, where his family had relocated. Hubble also spent time as a teacher of Spanish, Physics, and Mathematics, and a coach of basketball at New Albany High School in Indiana, but he soon found himself longing to return to the field of science. When the school term ended in 1914, Hubble went back to the University of Chicago for postgraduate studies and took a research post at the Yerkes Observatory. He received his doctorate in astronomy in 1917. Hubble was quite popular during his brief time spent teaching, as illustrated by this yearbook dedication:

"To Edwin P. Hubble, Our beloved teacher of Spanish and Physics, who has been a loyal friend to us in our senior year, ever willing to cheer and help us both in school and on the field, we, the class of 1914, lovingly dedicate this book."

Off to War

While finishing up the work for his doctorate in 1917, George Ellery Hale had invited Hubble to join the staff of Mount Wilson Observatory in Pasadena, California. Hubble spent an entire night finishing his thesis, completed the oral defense of his dissertation the following morning, and then proceeded to enlist in the U.S. Army a few days later. He sent a telegraph to Hale, saying: "Regret cannot accept your invitation. Am off to the war."

Hubble served as a captain in the 343rd Infantry, 86th Division, and eventually earned the rank of major. He was commissioned to France, where he spent time as a field and line officer. Returning to the United States in the summer of 1919, Hubble traveled immediately to the Mount Wilson Observatory and accepted a position there. Founded by Hale in Pasadena in 1904, Mount Wilson Observatory was, in Hubble's time, the center of observational work on astrophysics. It had the two largest and most powerful telescopes in the world in the 60-inch and 100-inch Hooker reflectors.

Hazy Blobs

During his time at the Yerkes as a postgrad, Hubble began studying faint, hazy patches of light in the sky called nebulae (from the Latin word for cloud). The word "nebula" is today used to describe clouds of dust and gas within galaxies, but in Hubble's time, astronomers hadn't been able to distinguish nebulae from distant galaxies, which also appeared as cloudy patches. Edwin became interested in two particular nebulae: the Large Magellanic Cloud and the Small Magellanic Cloud.

Working in 1912, American astronomer Henrietta Leavitt used the degree of brightness of Cepheid stars—stars whose brightness vary at regular intervals—in the Magellanic Clouds to measure their distance from the Earth. The longer the time a Cepheid star takes to undergo a complete cycle, the higher the star's average brightness or average "absolute magnitude." Leavitt was able to determine the distance from Earth to the nebula by comparing the brightness of the star as seen from Earth with the star's actual brightness, which was estimated using the length of the star's cycle. With this work, Leavitt and her colleagues demonstrated that the Magellanic Clouds existed beyond the Milky Way's boundaries.

Beyond the Milky Way

Astronomer Harlow Shapley, who also worked at Mount Wilson and was a rival to Hubble, had already made a name for himself by measuring the size of the Milky Way. Shapley used Leavitt's method that relied on Cepheid brightness to establish the distance of the galaxy, and he, like a majority of astronomers at that time, thought the Milky Way made up the entire universe.

Hubble made great strides in his study of nebulae with Mount Wilson's Hooker telescope at his disposal, and worked many long nights with janitor-turned-night-assistant Milton Lasell Humason to try to prove Shapley wrong. He aimed the telescope at nebulae thought to be outside the Milky Way galaxy, and searched for Cepheid stars in them. In October 1923, he discovered a Cepheid, or variable star, in the Andromeda Nebula. Hubble identified 12 Cepheid stars in this Andromeda Galaxy within a year, and was able to conclude that Andromeda was approximately 900,000 light years away from the Earth. Since the Milky Way's diameter was known to be only a few hundred thousand light years across as established by Shapley, Hubble's measurements demonstrated that Andromeda was significantly outside the limits of Earth's galaxy. By 1924, Hubble proposed that these and other far away nebulae were indeed other galaxies just like the Milky Way, and this theory became known as the "island universe."

1924 was an eventful year for Edwin Hubble on a personal level as well. He married Grace Burke in Pasadena on February 26.

Constant Expansion

Literally overnight, Hubble had discovered the cosmos. He went on observing nebulae, and set up a classification system for all known galaxies according to their distance, shape, contents, size, and brightness. Hubble made another incredible find in 1929 by observing "redshifts" in the light wavelengths emitted by galaxies: all galaxies appear to recede from us, and there is a relationship between a galaxy's distance from us and its velocity through space. In other words, the farther away a galaxy is from Earth, the faster it is racing away from us. This became known as Hubble's Law, and is interpreted as evidence that the universe is constantly expanding. Hubble's Law became a central idea behind the big bang theory.

More than ten years prior to Hubble's find, Albert Einstein had already set out his general relativity theory, and produced a model of space based on it, which claimed that space was curved by gravity and therefore must be capable of expansion and contraction. But Einstein had caved to the observational wisdom of the day and changed his original equations. With the discovery of Hubble's Law, Edwin had proved Albert right. Einstein paid a special visit to Hubble at Mount Wilson in 1931 to thank him for his work, and said that second-guessing his original findings was "the greatest blunder of my life."

Between 1922 and 1936, Hubble had solved several of the central problems concerning the nature of the universe and laid the foundations of cosmology with his work.

A Great Honor

Hubble continued his work at Mount Wilson until 1942, when he sought to join the fight against the Nazis in World War II. He was involved in war duties at the Aberdeen Proving Ground in Maryland, and his work there earned him the 1946 Medal of Merit for outstanding contribution to ballistics research.

Back in Pasadena after the war, Hubble was a member of the Mount Wilson advisory committee for development of the 200-inch Hale telescope and played a central role in its design. When construction of the telescope was completed at Mount Palomar Observatory, Hubble was given the great honor of being the first person to observe with it. The Hale telescope was four times as powerful as the Hooker telescope, and was the largest on Earth for several decades.

Hubble continued his research at Mount Wilson and Mount Palomar observatories until his death in San Marino, California, on September 28, 1953, from a cerebral thrombosis. He was 64 years old.

An Important Question

In 1919, when Edwin Hubble first began his work in the field of astronomy, there was an ongoing debate whether Earth's home, the Milky Way galaxy, made up the whole universe, or whether it was just one of many galaxies inhabiting a much greater space. But without better telescopes, scientists couldn't come to a resolution. Hubble was fortunate enough to conduct his research at Mount Wilson Observatory, using the largest and most powerful telescope in the world.

Hubble's research involved an important question that astronomers hadn't been able to answer up to that point. What are nebulae? Setting his sights on Andromeda Nebula, Hubble was able to detect Cepheid stars within it, and applying Henrietta Leavitt's pioneering work using Cepheid stars as a measure of distance, determined that the Andromeda Cepheids were much too far away to be part of the Milky Way galaxy. He concluded that Andromeda Nebula wasn't a cloud of gas within the Milky Way at all, but rather an "island universe"—an entirely different galaxy. Hubble settled the ongoing debate with his discovery that the Milky Way is but one of millions of galaxies, and forever changed man's view of the universe.

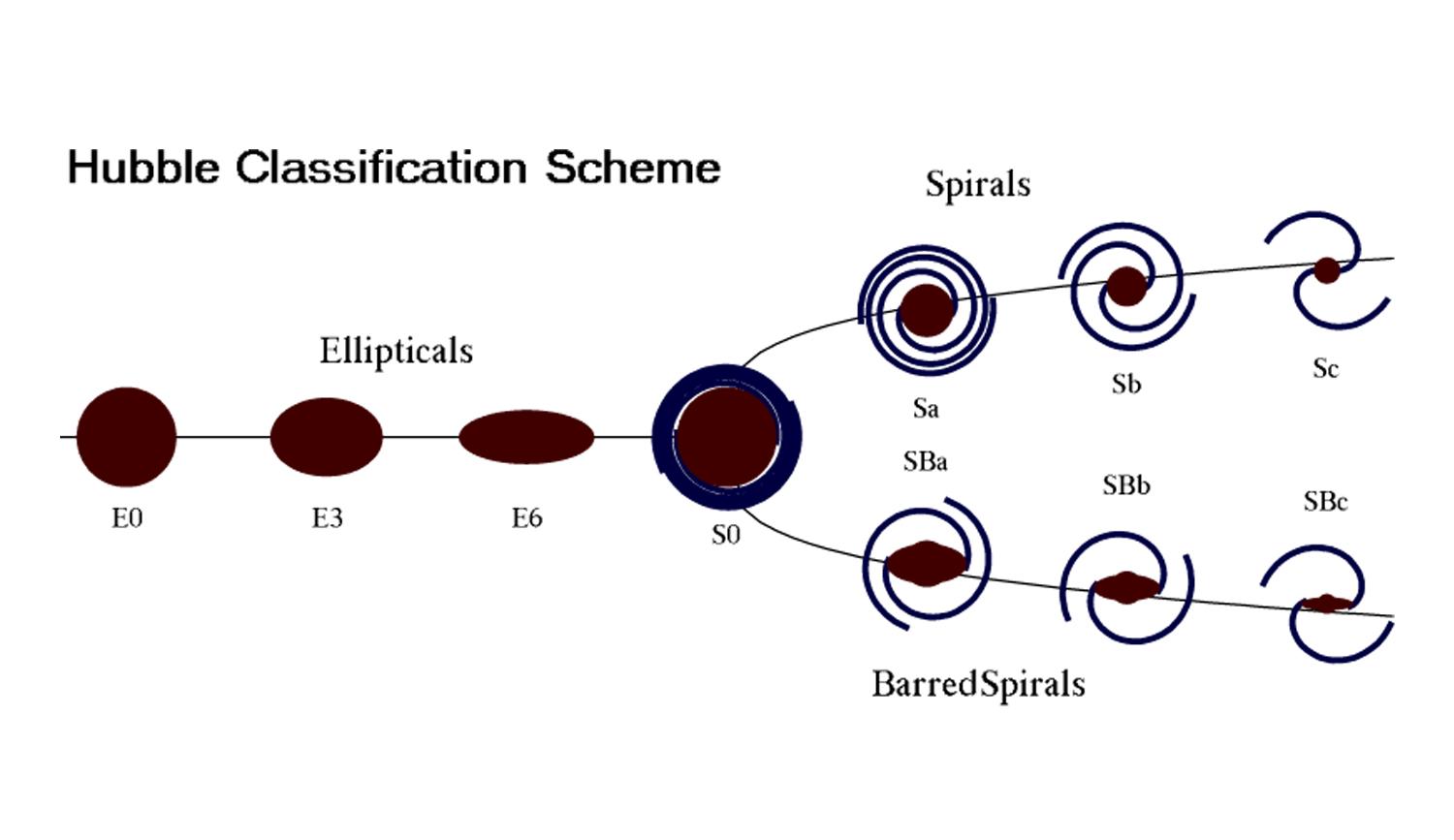

Classification

Edwin Hubble continued his observations and found galaxies at increasingly further distances. He devised a classification system, known as the Hubble sequence, for these galaxies using pictures he took of their structure through his telescope. This is a system that is still used today. Galaxies are generally classified based on overall shape: elliptical, spiral, or barred spiral. Further classification is given depending on certain properties of the specific galaxy (for example, the degree of its ellipse). Elliptical galaxies are generally characterized by random motion and an older population of stars. Spiral galaxies are composed of a central bulge (contains older stars) surrounded by a disk (young stars and open star clusters), and have bright arms of star formation within the disk that entend from the bulge. Barred spiral galaxies are spiral galaxies with a band of bright stars that emerge from the center and extend across the middle of it. Spiral arms emerge from the ends of the "bar," as opposed to emerging from the core of ordinary spiral galaxies. Earth's galaxy, the Milky Way, has been classified as a barred spiral galaxy (SBb).

Also called the Hubble "tuning fork" diagram it reads from left to right with elliptical galaxies as the base. The ellipticals can be named E0 through E7, with the number indicating the degree of the oval shape of the ellipse ("0" is ball-shaped and "7" is discus-shaped).

The spiral branch is indicated as follows:

- "0" means no arms

- Sa - tightly-wound, smooth arms, and a bright central disc

- Sb - better defined spiral arms than Sa

- Sc - much more loosely wound spiral arms than Sb

- Sd - very loose arms, most of the luminosity is in the arms and not the disc

The barred spiral branch is indicated as follows:

- SBa - a bright center and tight spirals

- SBb - better defined arms than SBa galaxy and are more loosely wound

- SBc - even looser arms, and a much dimmer central portion of the galaxy

Irregular galaxies can show spiral structure but are deformed in some way, and do not fit into other categories.

Hubble's Law

From Earth, the spectra of light given off by celestial objects shifts depending on their movement toward or away from the Earth. Galaxies that move toward Earth shift toward the blue end of the light spectrum and galaxies moving away from Earth shift toward the red end of the light spectrum. Combining his work with astronomer Vesto Slipher's earlier measurements of the "redshifts," Hubble plotted distances of galaxies and uncovered a direct relationship. The galaxies were receding from Earth at a rate proportional to their distance from Earth. Hubble determined that the farther away a galaxy, the greater its redshift. Or, the greater the distance between a galaxy and Earth, the faster that galaxy is racing away from Earth. The greater the distance between two galaxies, the faster they were moving away from one another. This proportionality between distance and speed of galaxies was formulated in 1929 by Hubble and Humason, and is known as Hubble's Law. It was an extraordinary discovery; one that meant that the universe was constantly expanding.

The mathematical equation for Hubble's law is as follows:

v = H0D

The velocity of recession (V), expressed in km/s, is directly proportional to distance (D), measured in megaparsecs/Mpc, where H0 is the value of the Hubble constant at the time of observation in the history of the universe. (A megaparsec is 3.26 million light-years.)

The Hubble Constant

The Hubble constant is one of the most critical numbers to the science of cosmology because it is necessary for estimating the size and age of the universe. The long-sought number is in constant debate, and indicates the rate at which the universe is expanding, from the point of the big bang. The Hubble Constant is represented by the mathematical equation, HO = v/d, where v is the galaxy's radial outward velocity, d is the galaxy's distance from Earth, and HO is the current value of the Hubble Constant. Determining a true value for the Hubble constant is quite complex, as astronomers need two measurements. For the first, observations must reveal the galaxy's redshift, indicating the radial velocity. The second is more difficult to determine, and is the galaxy's precise distance from the Earth.

The value of the Hubble Constant first obtained by Edwin Hubble was approximately 500 km/sec/Mpc, and has since been dramatically revised. The values currently proposed by different experimental and theoretical groups range from 50 to 100 km/sec/Mpc.

With a Bang

Hubble took his discovery to the next level. If galaxies twice as far away were moving away from one another at twice the speed, they must have started their expansion from the same space and time. Hubble determined, using his ratio of distance to speed, that that time was approximately two billion years ago. By today's figurings, he miscalculated by more than ten billion years, but with his estimates he laid the groundwork for the big bang theory, lending evidence to the theory that the universe has been expanding ever since it began with a tremendous burst of energy.

Acknowledgement

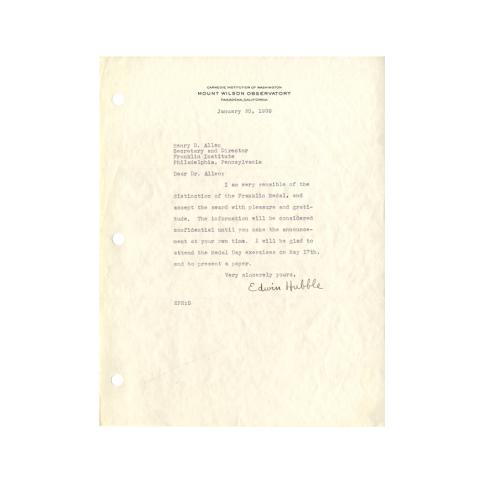

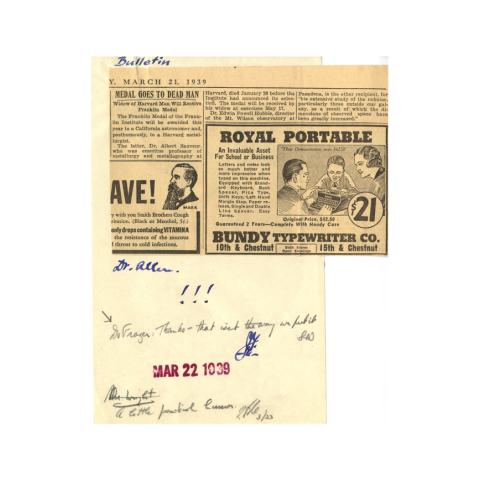

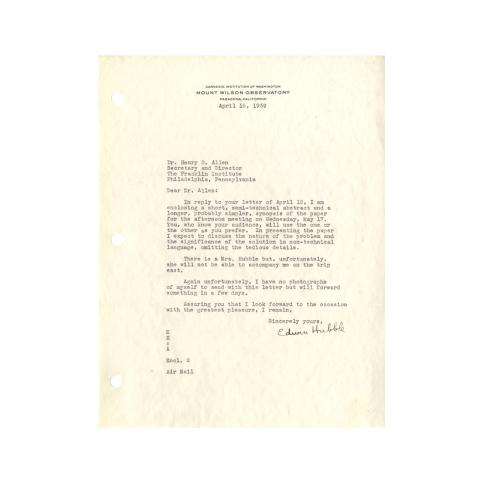

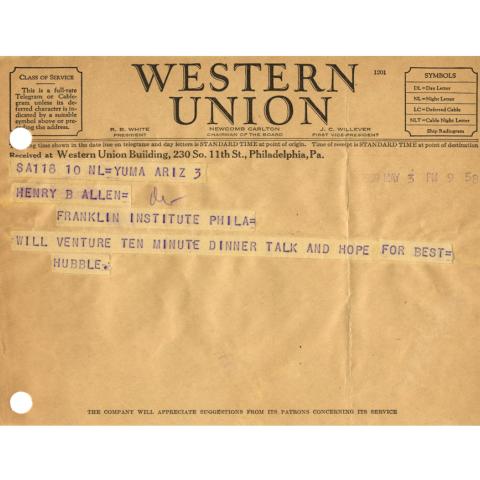

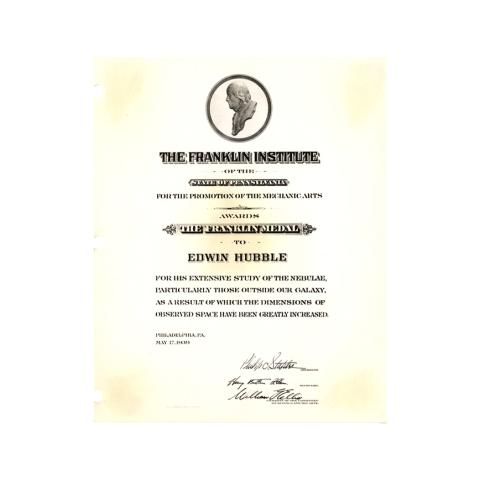

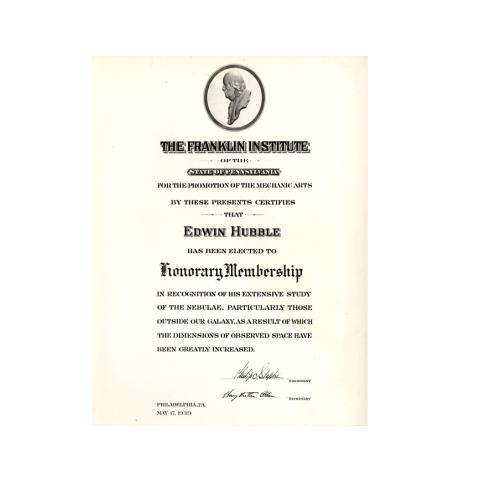

Edwin Hubble was awarded the 1939 Franklin Medal in Physics for "his extensive study of the nebulae, particularly those outside our galaxy, as a result of which the dimensions of observed space have been greatly increased."

Other awards and honors bestowed on Hubble include:

- The 1938 Catherine Wolfe Bruce gold medal, awarded yearly by the Astronomical Society of the Pacific for outstanding lifetime contributions to astronomy

- The 1940 Gold Medal of the Royal Astronomical Society

- A 1946 Medal of Merit for outstanding contribution to ballistics research, more specifically for "exceptional conduct in providing outstanding services to citizens" during World War II

- 1948 election as an Honorary Fellow of Queen's College, Oxford, for notable contributions to astronomy

- Asteroid 2069 Hubble, discovered by Indiana University astronomers in 1955, is named for Edwin Powell Hubble, as is the Hubble crater on the Moon and the Hubble Space Telescope.

In the latter part of his career, Hubble campaigned heartily for astronomy to be considered an area of physics rather than its own discipline. This was primarily so that he and fellow astronomers could be recognized by the Nobel Prize Committee for contributions to astrophysics. Even though Hubble was unsuccessful for many years, the Committee eventually decided that work in the field of astronomy could be eligible for the Nobel Prize in physics. However, the decision came too late for Hubble; it was made a few months after his death in 1953. The Nobel Prize has never been awarded posthumously.

Credits

The Edwin Hubble presentation is made possible by support from The Barra Foundation and Unisys.

This website is the effort of an in-house special project team at The Franklin Institute, working under the direction of Carol Parssinen, Senior Vice-President for the Center for Innovation in Science Learning, and Bo Hammer, Vice-President for The Franklin Center.

Special project team members from the Educational Technology department are:

Karen Elinich, Barbara Holberg, Margaret Ennis, and Zach Williams.

Special project team members from the Curatorial department are:

John Alviti and Elisa Graydon.

The project's Advisory Board Members are:

Ruth Schwartz-Cowan, Leonard Rosenfeld, Nathan Ensmenger, and Susan Yoon.

Read the Committee on Science and the Arts Report on Edwin Hubble’s early life and his work in the field of Astronomy.