PHILADELPHIA WOMEN IN SCIENCE

We're kicking off a new Philadelphia Women in Science series, featuring women on the front lines of science doing exciting work in genetics, chemistry, marine biology, and much more. First up is Dr. Loni Tabb, who is using biostatistics—data relating to living organisms—to understand public health challenges.

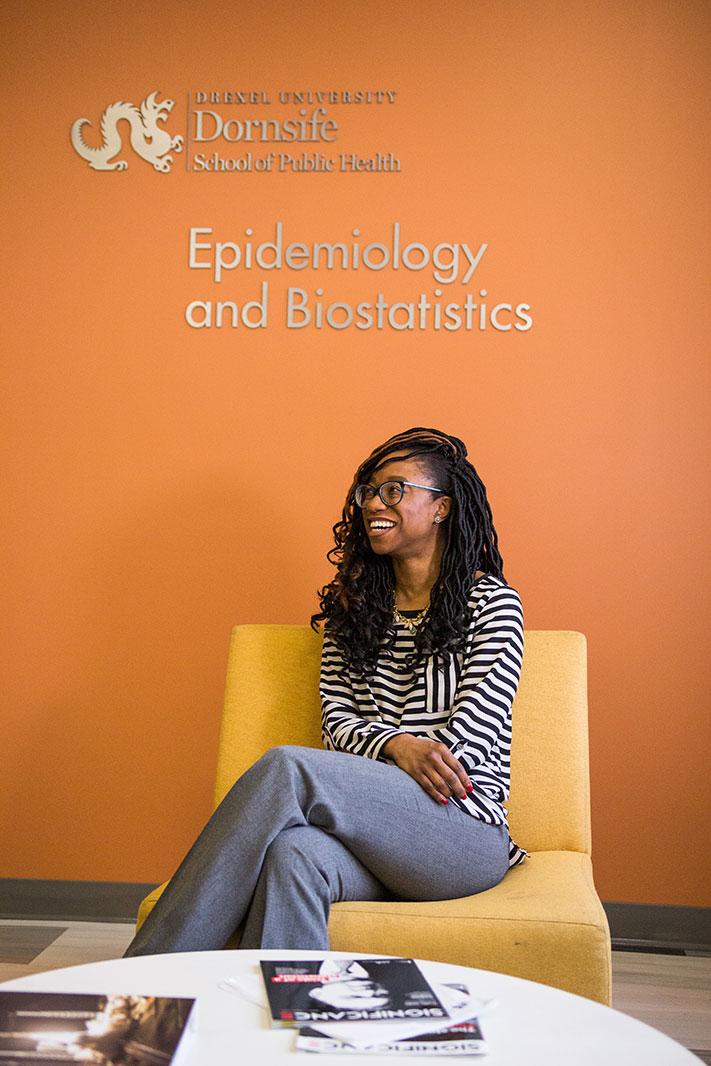

Who: Loni Philip Tabb, Ph.D.

Associate Professor of Biostatistics

Dornsife School of Public Health, Department of Epidemiology and Biostatistics

Drexel University, Philadelphia

Tell us about your current work.

My research focuses on using spatial statistics and spatial epidemiology (think maps!) to examine a variety of public health challenges we face here in this country. My goal is to drive home the point that where people eat, sleep, work, learn, and play impacts their health and ultimately their lives.

Specifically, much of my earlier research examined the relationship between the violence that occurs in neighborhoods and the presence of alcohol outlets (i.e. beer distributors, restaurants, nightclubs, etc.). Not only did this research show that violence is more pronounced, unfortunately, in neighborhoods that have more minorities, are more disadvantaged, and have other risky retailers (i.e. pawn shops), but this work also shows that this relationship between alcohol and violence persists in neighborhoods that have significant alcohol-related policies allowing for more alcohol availability in these neighborhoods.

Another area of my research, which still uses spatial statistics and spatial epidemiology methods, focuses on the patterning across the U.S. of cardiovascular health disparities between blacks and whites. This new area of research allows for a more in-depth analysis of where these disparities are the greatest in our country, with a future focus on how these disparities have changed over time (especially considering the various cardiovascular health interventions that have been implemented across the country, i.e., smoking bans in public spaces, updated physical activity guidelines, as well as dietary guidelines).

How did you get into science?

When I first entered as a freshman at Drexel University (1998), my major was business administration. During my sophomore year, I worked as an analyst at the Vanguard Group, which is one of the world's largest investment companies. This position allowed me to gain analytic skills in dealing with mutual fund investments; however, while training for the position, the analyst training me pulled me aside and asked why I was not pursuing math for my actual degree. That one small conversation changed my life. That year, my sophomore year, was the first time I jumped into the world of science—by way of math.

Do you have a mentor?

I have a village of mentors, both professional and personal—including my parents, who were both immigrants (from St. Vincent and Grenadines, Mom, and Grenada, Dad) to this country and created options for me and my brother, where education was always a priority in our household.

One mentor, though, early on in my academic training was Dr. Ewaugh Finney Fields. She was the first female African-American mathematician that I had the privilege to meet, work with, and ultimately walk in her footsteps while here at Drexel as an undergraduate and graduate student. When I switched majors from business administration to math, the challenges I faced in the classroom were, at times, unbearable (to say the least).

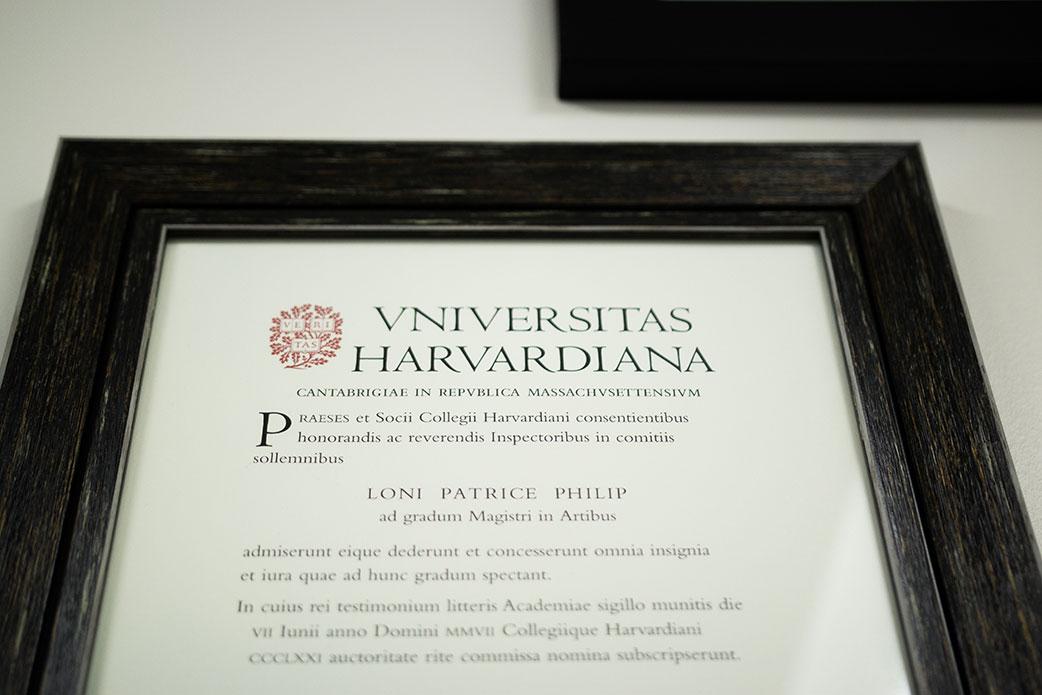

Often I was the only female in a classroom of all males, in addition to being the only African-American. I felt like a complete outsider. But Dr. Fields, who was a professor in the Math Department at the time, was instrumental in my success through the program. She often reminded me of my purpose as a student and she singlehandedly forced me to apply to graduate school at Harvard University to obtain my Ph.D. in biostatistics. Harvard was not on the list of schools I ever imagined I would attend, let alone apply to. It was because of her vision, her courage, her determination, and her support that I changed for the challenges that were ahead of me.

Dr. Fields has since passed away, but I was able to celebrate her life with close family and friends earlier this year. She was truly a fearless leader in the field, and definitely a modern-day "Hidden Figure."

What are the biggest challenges you face in your field?

One of the biggest challenges I face in my field is still the lack of diversity. Although our field has made strides in trying to increase the numbers of minorities in the field of biostatistics, we still have a very long way to go. I'd like to think that my daughter (six years old) and my son (three years old) will see more and more individuals that look like them in as many fields as possible, but I'm obviously biased toward the STEM fields. Not seeing leaders in the STEM field that resemble you as a child shows the wrong message—it shows that you don't belong, that you're not welcomed, that you're not allowed. We need to diversify the landscape of our field to include individuals from all walks of life, from different backgrounds, from different perspectives.

How can we get more girls interested in STEM?

I think it starts at home. We need our girls to know from a very early age that STEM is an area for them, just as it is for our boys. Early on, we, as a society, push certain norms onto our children, which ultimately determines their paths. At home, my daughter is encouraged to think more critically, build knowing things may fall apart, and take calculated risks that will allow her to succeed in the STEM field—if she were to choose that path. She may not know it just yet, but I want her to see and know that STEM will be an option for her.

What's your favorite piece of scientific trivia?

One of my favorite pieces of scientific trivia that I encountered in my first probability class at Harvard University was the Birthday Problem (also known as the Birthday Paradox). The professor for my class started off by asking each student to guess how many people are needed to be in a room before we find a pair of individuals that share the same birthday. My initial guess was 365 people. I was obviously wrong, because in as few as 23 people, the likelihood of getting a pair of individuals with the same birthday is around the flip of a coin. And you only need roughly 70 folks crammed in a room to be 100 percent certain there’s at least one pair that share the same birthday.

What's something interesting that people may not know about you?

I'd like to open a modeling agency for all types of models regardless of age, race, sex, size, faith, income, etc. I started out as a model at a very young age, and modeling and fashion have always stayed with me, regardless of where the math leads me.

March 13, 2018. Interview by Nancy Gupton. Edited for length and clarity.

More Philadelphia Women in Science

Dr. Ileana Pérez-Rodríguez: Unlocking Microbial Mysteries at the Bottom of the Ocean

Fighting to Flush Hepatitis C Out of Philadelphia: Dr. Stacey Trooskin