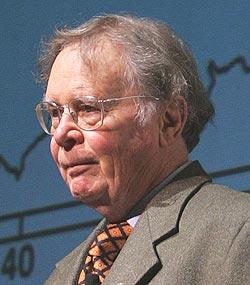

For pioneering research leading to an understanding of the ocean's influence on climate change. His work led to the successful development of a comprehensive picture of ocean circulation and its role in both past and future environmental change.

The first theories that humans could affect the earth's climate appeared over 100 years ago, but it was Wallace Broecker who was so influential in the science of human-induced climate change.

Born in Chicago in 1931, Broecker earned his undergraduate degree in physics and his PhD in geology from Columbia University at a time when geologists and oceanographers were just beginning to study global climate. In 1959 he became an assistant professor at Columbia, where he has worked ever since. One of Broecker's first projects was to measure and track the radioactive carbon content of ocean water and sediments to decipher how ocean currents move over time. Dating the sediments provided some of the first insights into climate history; Broecker discovered that the last ice age had ended a mere 11,000 years ago. Broecker began to study what could trigger such change. His previous work in ocean currents led to a hypothesis: he described what is now called Broecker's Conveyor—a circulating ribbon of water that carries warm water northward on the surface of the ocean, and deep, cold water southward. This conveyor helps maintain the climate by absorbing both global heat and the planet's extra carbon dioxide—the mixing of the water constantly sends new water to the surface ready for that crucial absorption. Broecker theorized that if the conveyor turns off by, say, polar ice caps melting and flooding the system, it might send the climate skidding out of equilibrium over the period of just a couple of decades.

Because of his continued work in tracing the way chemicals and water move through the ocean, Broecker is outspoken on the potential dangers of global warming. He is often quoted as describing the planet as "an angry beast that we're poking with a stick." He also continues to work on ways to remove additional carbon dioxide from the atmosphere and safely bury it deep in the ground.

Still teaching at Columbia, Broecker has written over 500 journal articles and nine books. He has earned numerous distinguished honors, including the National Medal of Science, the Alexander Agassiz Medal of the National Academy of Sciences, the Vetlesen Prize from the G. Unger Vetlesen Foundation, the Wollaston Medal of the Geological Society of London, the Blue Planet Prize from The Asahi Glass Foundation, the Geological Society of America's Don J. Easterbrook Distinguished Scientist Award, the University of Southern California's Tyler Prize for Environmental Achievement and the Crafoord Prize in Geoscience. He is a member of the National Academy of Sciences.

Information as of April 2008